Lets say we have following sample code in C#:

class BaseClass

{

public virtual void HelloWorld()

{

Console.WriteLine("Hello Tarik");

}

}

class DerivedClass : BaseClass

{

public override void HelloWorld()

{

base.HelloWorld();

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

DerivedClass derived = new DerivedClass();

derived.HelloWorld();

}

}

When I ildasmed the following code:

.method private hidebysig static void Main(string[] args) cil managed

{

.entrypoint

// Code size 15 (0xf)

.maxstack 1

.locals init ([0] class EnumReflection.DerivedClass derived)

IL_0000: nop

IL_0001: newobj instance void EnumReflection.DerivedClass::.ctor()

IL_0006: stloc.0

IL_0007: ldloc.0

IL_0008: callvirt instance void EnumReflection.BaseClass::HelloWorld()

IL_000d: nop

IL_000e: ret

} // end of method Program::Main

However, csc.exe converted derived.HelloWorld(); --> callvirt instance void EnumReflection.BaseClass::HelloWorld(). Why is that? I didn't mention BaseClass anywhere in the Main method.

And also if it is calling BaseClass::HelloWorld() then I would expect call instead of callvirt since it looks direct calling to BaseClass::HelloWorld() method.

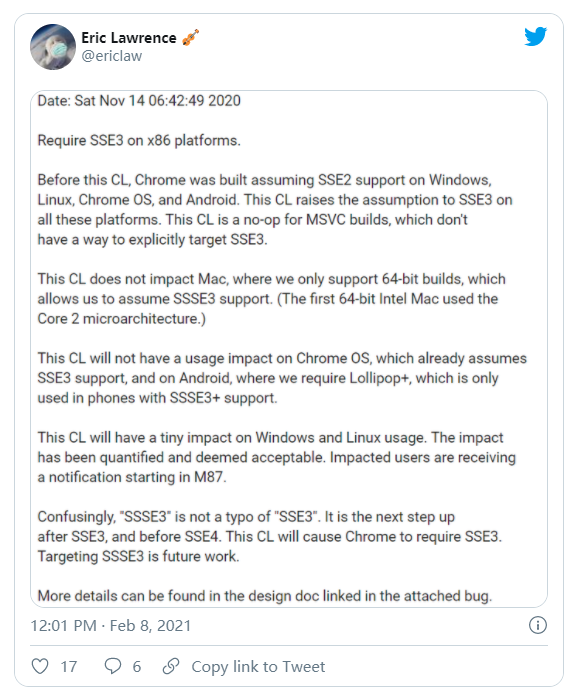

The call goes to BaseClass::HelloWorld because BaseClass is the class that defines the method. The way virtual dispatch works in C# is that the method is called on the base class, and the virtual dispatch system is responsible for ensuring that the most-derived override of the method gets called.

This answer of Eric Lippert's is very informative: https://stackoverflow.com/a/5308369/385844

As is his blog series on the topic: http://blogs.msdn.com/b/ericlippert/archive/tags/virtual+dispatch/

Do you have any idea why this is implemented this way? What would happen if it was calling derived class ToString method directly? This way didnt much sense this to me at first glance...

It's implemented this way because the compiler does not track the runtime type of objects, just the compile-time type of their references. With the code you posted, it's easy to see that the call will go to the DerivedClass implementation of the method. But suppose the derived variable was initialized like this:

Derived derived = GetDerived();

It's possible that GetDerived() returns an instance of StillMoreDerived. If StillMoreDerived (or any class between Derived and StillMoreDerived in the inheritance chain) overrides the method, then it would be incorrect to call the Derived implementation of the method.

To find all possible values a variable could hold through static analysis is to solve the halting problem. With a .NET assembly, the problem is even worse, because an assembly might not be a complete program. So, the number of cases where the compiler could reasonably prove that derived doesn't hold a reference to a more-derived object (or a null reference) would be small.

How much would it cost to add this logic so it can issue a call rather than callvirt instruction? No doubt, the cost would be far higher than the small benefit derived.

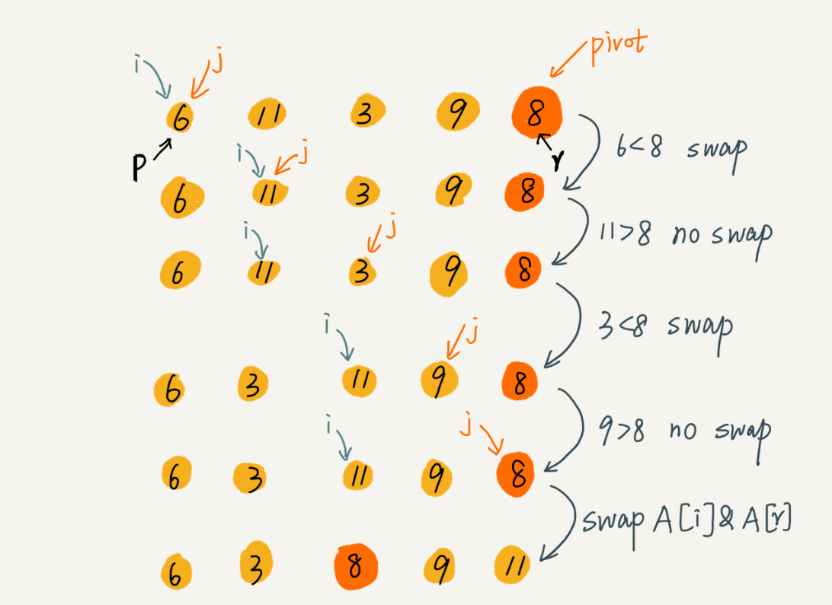

The way to think about this is that virtual methods define a "slot" that you can put a method into at runtime. When we emit a callvirt instruction we are saying "at runtime, look to see what is in this slot and invoke it".

The slot is identified by the method information about the type that declared the virtual method, not the type that overrides it.

It would be perfectly legal to emit a callvirt to the derived method; the runtime would realize that the derived method is the same slot as the base method and the result would be exactly the same. But there is never any reason to do that. It is more clear if we identify the slot by identifying the type that declares that slot.

Note that this happens even if you declare DerivedClass as sealed.

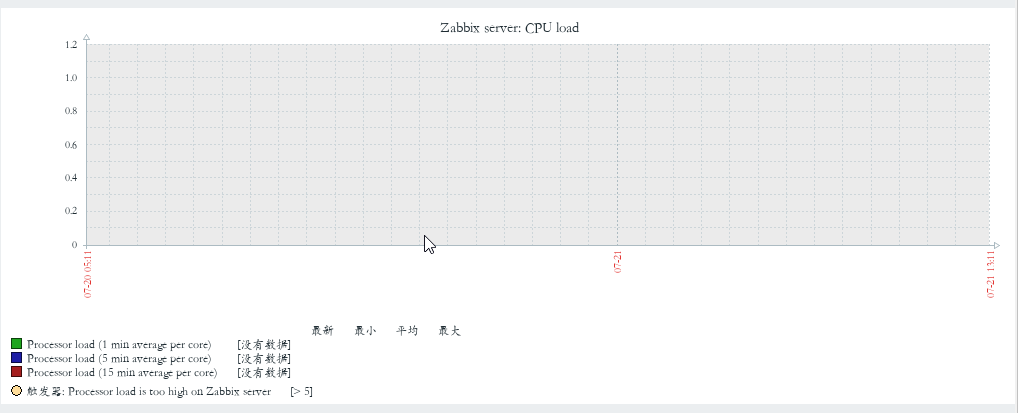

C# uses the callvirt operator to call any instance method (virtual or not) to automatically get a null check on the object reference - to raise a NullReferenceException at the point that a method is called. Otherwise, the NullReferenceException will only be raised at the first actual use of any instance member of the class inside the method, which can be surprising. If no instance member is used, the method could actually complete successfully without ever raising the exception.

You should also remember that IL is not executed directly. It is first compiled to native instructions by the JIT compiler - and that performs a number of optimizations depending on whether you're debugging the process. I found that the x86 JIT for CLR 2.0 inlined a non-virtual method but called the virtual method - it also inlined Console.WriteLine!