A coworker just told me that the C# Dictionary collection resizes by prime numbers for arcane reasons relating to hashing. And my immediate question was, "how does it know what the next prime is? do they story a giant table or compute on the fly? that's a scary non-deterministic runtime on an insert causing a resize"

So my question is, given N, which is a prime number, what is the most efficient way to compute the next prime number?

The gaps between consecutive prime numbers is known to be quite small, with the first gap of over 100 occurring for prime number 370261. That means that even a simple brute force will be fast enough in most circumstances, taking O(ln(p)*sqrt(p)) on average.

For p=10,000 that's O(921) operations. Bearing in mind we'll be performing this once every O(ln(p)) insertion (roughly speaking), this is well within the constraints of most problems taking on the order of a millisecond on most modern hardware.

About a year ago I was working this area for libc++ while implementing the

unordered (hash) containers for C++11. I thought I would share

my experiences here. This experience supports marcog's accepted answer for a

reasonable definition of "brute force".

That means that even a simple brute force will be fast enough in most

circumstances, taking O(ln(p)*sqrt(p)) on average.

I developed several implementations of size_t next_prime(size_t n) where the

spec for this function is:

Returns: The smallest prime that is greater than or equal to n.

Each implementation of next_prime is accompanied by a helper function is_prime. is_prime should be considered a private implementation detail; not meant to be called directly by the client. Each of these implementations was of course tested for correctness, but also

tested with the following performance test:

int main()

{

typedef std::chrono::high_resolution_clock Clock;

typedef std::chrono::duration<double, std::milli> ms;

Clock::time_point t0 = Clock::now();

std::size_t n = 100000000;

std::size_t e = 100000;

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < e; ++i)

n = next_prime(n+1);

Clock::time_point t1 = Clock::now();

std::cout << e/ms(t1-t0).count() << " primes/millisecond\n";

return n;

}

I should stress that this is a performance test, and does not reflect typical

usage, which would look more like:

// Overflow checking not shown for clarity purposes

n = next_prime(2*n + 1);

All performance tests were compiled with:

clang++ -stdlib=libc++ -O3 main.cpp

Implementation 1

There are seven implementations. The purpose for displaying the first

implementation is to demonstrate that if you fail to stop testing the candidate

prime x for factors at sqrt(x) then you have failed to even achieve an

implementation that could be classified as brute force. This implementation is

brutally slow.

bool

is_prime(std::size_t x)

{

if (x < 2)

return false;

for (std::size_t i = 2; i < x; ++i)

{

if (x % i == 0)

return false;

}

return true;

}

std::size_t

next_prime(std::size_t x)

{

for (; !is_prime(x); ++x)

;

return x;

}

For this implementation only I had to set e to 100 instead of 100000, just to

get a reasonable running time:

0.0015282 primes/millisecond

Implementation 2

This implementation is the slowest of the brute force implementations and the

only difference from implementation 1 is that it stops testing for primeness

when the factor surpasses sqrt(x).

bool

is_prime(std::size_t x)

{

if (x < 2)

return false;

for (std::size_t i = 2; true; ++i)

{

std::size_t q = x / i;

if (q < i)

return true;

if (x % i == 0)

return false;

}

return true;

}

std::size_t

next_prime(std::size_t x)

{

for (; !is_prime(x); ++x)

;

return x;

}

Note that sqrt(x) isn't directly computed, but inferred by q < i. This

speeds things up by a factor of thousands:

5.98576 primes/millisecond

and validates marcog's prediction:

... this is well within the constraints of

most problems taking on the order of

a millisecond on most modern hardware.

Implementation 3

One can nearly double the speed (at least on the hardware I'm using) by

avoiding use of the % operator:

bool

is_prime(std::size_t x)

{

if (x < 2)

return false;

for (std::size_t i = 2; true; ++i)

{

std::size_t q = x / i;

if (q < i)

return true;

if (x == q * i)

return false;

}

return true;

}

std::size_t

next_prime(std::size_t x)

{

for (; !is_prime(x); ++x)

;

return x;

}

11.0512 primes/millisecond

Implementation 4

So far I haven't even used the common knowledge that 2 is the only even prime.

This implementation incorporates that knowledge, nearly doubling the speed

again:

bool

is_prime(std::size_t x)

{

for (std::size_t i = 3; true; i += 2)

{

std::size_t q = x / i;

if (q < i)

return true;

if (x == q * i)

return false;

}

return true;

}

std::size_t

next_prime(std::size_t x)

{

if (x <= 2)

return 2;

if (!(x & 1))

++x;

for (; !is_prime(x); x += 2)

;

return x;

}

21.9846 primes/millisecond

Implementation 4 is probably what most people have in mind when they think

"brute force".

Implementation 5

Using the following formula you can easily choose all numbers which are

divisible by neither 2 nor 3:

6 * k + {1, 5}

where k >= 1. The following implementation uses this formula, but implemented

with a cute xor trick:

bool

is_prime(std::size_t x)

{

std::size_t o = 4;

for (std::size_t i = 5; true; i += o)

{

std::size_t q = x / i;

if (q < i)

return true;

if (x == q * i)

return false;

o ^= 6;

}

return true;

}

std::size_t

next_prime(std::size_t x)

{

switch (x)

{

case 0:

case 1:

case 2:

return 2;

case 3:

return 3;

case 4:

case 5:

return 5;

}

std::size_t k = x / 6;

std::size_t i = x - 6 * k;

std::size_t o = i < 2 ? 1 : 5;

x = 6 * k + o;

for (i = (3 + o) / 2; !is_prime(x); x += i)

i ^= 6;

return x;

}

This effectively means that the algorithm has to check only 1/3 of the

integers for primeness instead of 1/2 of the numbers and the performance test

shows the expected speed up of nearly 50%:

32.6167 primes/millisecond

Implementation 6

This implementation is a logical extension of implementation 5: It uses the

following formula to compute all numbers which are not divisible by 2, 3 and 5:

30 * k + {1, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29}

It also unrolls the inner loop within is_prime, and creates a list of "small

primes" that is useful for dealing with numbers less than 30.

static const std::size_t small_primes[] =

{

2,

3,

5,

7,

11,

13,

17,

19,

23,

29

};

static const std::size_t indices[] =

{

1,

7,

11,

13,

17,

19,

23,

29

};

bool

is_prime(std::size_t x)

{

const size_t N = sizeof(small_primes) / sizeof(small_primes[0]);

for (std::size_t i = 3; i < N; ++i)

{

const std::size_t p = small_primes[i];

const std::size_t q = x / p;

if (q < p)

return true;

if (x == q * p)

return false;

}

for (std::size_t i = 31; true;)

{

std::size_t q = x / i;

if (q < i)

return true;

if (x == q * i)

return false;

i += 6;

q = x / i;

if (q < i)

return true;

if (x == q * i)

return false;

i += 4;

q = x / i;

if (q < i)

return true;

if (x == q * i)

return false;

i += 2;

q = x / i;

if (q < i)

return true;

if (x == q * i)

return false;

i += 4;

q = x / i;

if (q < i)

return true;

if (x == q * i)

return false;

i += 2;

q = x / i;

if (q < i)

return true;

if (x == q * i)

return false;

i += 4;

q = x / i;

if (q < i)

return true;

if (x == q * i)

return false;

i += 6;

q = x / i;

if (q < i)

return true;

if (x == q * i)

return false;

i += 2;

}

return true;

}

std::size_t

next_prime(std::size_t n)

{

const size_t L = 30;

const size_t N = sizeof(small_primes) / sizeof(small_primes[0]);

// If n is small enough, search in small_primes

if (n <= small_primes[N-1])

return *std::lower_bound(small_primes, small_primes + N, n);

// Else n > largest small_primes

// Start searching list of potential primes: L * k0 + indices[in]

const size_t M = sizeof(indices) / sizeof(indices[0]);

// Select first potential prime >= n

// Known a-priori n >= L

size_t k0 = n / L;

size_t in = std::lower_bound(indices, indices + M, n - k0 * L) - indices;

n = L * k0 + indices[in];

while (!is_prime(n))

{

if (++in == M)

{

++k0;

in = 0;

}

n = L * k0 + indices[in];

}

return n;

}

This is arguably getting beyond "brute force" and is good for boosting the

speed another 27.5% to:

41.6026 primes/millisecond

Implementation 7

It is practical to play the above game for one more iteration, developing a

formula for numbers not divisible by 2, 3, 5 and 7:

210 * k + {1, 11, ...},

The source code isn't shown here, but is very similar to implementation 6.

This is the implementation I chose to actually use for the unordered containers

of libc++, and that source code is open source (found at the link).

This final iteration is good for another 14.6% speed boost to:

47.685 primes/millisecond

Use of this algorithm assures that clients of libc++'s hash tables can choose

any prime they decide is most beneficial to their situation, and the performance

for this application is quite acceptable.

A nice trick is to use a partial sieve. For example, what is the next prime that follows the number N = 2534536543556?

Check the modulus of N with respect to a list of small primes. Thus...

mod(2534536543556,[3 5 7 11 13 17 19 23 29 31 37])

ans =

2 1 3 6 4 1 3 4 22 16 25

We know that the next prime following N must be an odd number, and we can immediately discard all odd multiples of this list of small primes. These moduli allow us to sieve out multiples of those small primes. Were we to use the small primes up to 200, we can use this scheme to immediately discard most potential prime numbers greater than N, except for a small list.

More explicitly, if we are looking for a prime number beyond 2534536543556, it cannot be divisible by 2, so we need consider only the odd numbers beyond that value. The moduli above show that 2534536543556 is congruent to 2 mod 3, therefore 2534536543556+1 is congruent to 0 mod 3, as must be 2534536543556+7, 2534536543556+13, etc. Effectively, we can sieve out many of the numbers without any need to test them for primality and without any trial divisions.

Similarly, the fact that

mod(2534536543556,7) = 3

tells us that 2534536543556+4 is congruent to 0 mod 7. Of course, that number is even, so we can ignore it. But 2534536543556+11 is an odd number that is divisible by 7, as is 2534536543556+25, etc. Again, we can exclude these numbers as clearly composite (because they are divisible by 7) and so not prime.

Using only the small list of primes up to 37, we can exclude most of the numbers that immediately follow our starting point of 2534536543556, only excepting a few:

{2534536543573 , 2534536543579 , 2534536543597}

Of those numbers, are they prime?

2534536543573 = 1430239 * 1772107

2534536543579 = 99833 * 25387763

I've made the effort of providing the prime factorizations of the first two numbers in the list. See that they are composite, but the prime factors are large. Of course, this makes sense, since we've already ensured that no number that remains can have small prime factors. The third one in our short list (2534536543597) is in fact the very first prime number beyond N. The sieving scheme I've described will tend to result in numbers that are either prime, or are composed of generally large prime factors. So we needed to actually apply an explicit test for primality to only a few numbers before finding the next prime.

A similar scheme quickly yields the next prime exceeding N = 1000000000000000000000000000, as 1000000000000000000000000103.

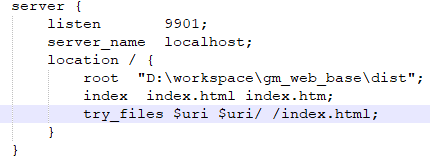

Just a few experiments with inter-primes distance.

This is a complement to visualize other answers.

I got the primes from the 100.000th (=1,299,709) to the 200.000th (=2,750,159)

Some data:

Maximum interprime distance = 148

Mean interprime distance = 15

Interprime distance frequency plot:

Interprime Distance vs Prime Number

Just to see it's "random". However ...

There's no function f(n) to calculate the next prime number. Instead a number must be tested for primality.

It is also very useful, when finding the nth prime number, to already know all prime numbers from the 1st up to (n-1)th, because those are the only numbers that need to be tested as factors.

As a result of these reasons, I would not be surprised if there is a precalculated set of large prime numbers. It doesn't really make sense to me if certain primes needed to be recalculated repeatedly.

For sheer novelty, there’s always this approach:

#!/usr/bin/perl

for $p ( 2 .. 200 ) {

next if (1x$p) =~ /^(11+)\1+$/;

for ($n=1x(1+$p); $n =~ /^(11+)\1+$/; $n.=1) { }

printf "next prime after %d is %d\n", $p, length($n);

}

which of course produces

next prime after 2 is 3

next prime after 3 is 5

next prime after 5 is 7

next prime after 7 is 11

next prime after 11 is 13

next prime after 13 is 17

next prime after 17 is 19

next prime after 19 is 23

next prime after 23 is 29

next prime after 29 is 31

next prime after 31 is 37

next prime after 37 is 41

next prime after 41 is 43

next prime after 43 is 47

next prime after 47 is 53

next prime after 53 is 59

next prime after 59 is 61

next prime after 61 is 67

next prime after 67 is 71

next prime after 71 is 73

next prime after 73 is 79

next prime after 79 is 83

next prime after 83 is 89

next prime after 89 is 97

next prime after 97 is 101

next prime after 101 is 103

next prime after 103 is 107

next prime after 107 is 109

next prime after 109 is 113

next prime after 113 is 127

next prime after 127 is 131

next prime after 131 is 137

next prime after 137 is 139

next prime after 139 is 149

next prime after 149 is 151

next prime after 151 is 157

next prime after 157 is 163

next prime after 163 is 167

next prime after 167 is 173

next prime after 173 is 179

next prime after 179 is 181

next prime after 181 is 191

next prime after 191 is 193

next prime after 193 is 197

next prime after 197 is 199

next prime after 199 is 211

All fun and games aside, it is well known that the optimal hash table size is rigorously provably a prime number of the form 4N−1. So just finding the next prime is insufficient. You have to do the other check, too.