I have been a .Net coder (can not say I am a programmer) for 2 years. There is one question that I can not understand for years, that is how could an instance of the base class hold an instance of the derived class?

Suppose we have two classes:

class BaseClass

{

public A propertyA;

public B propertyB;

}

class DerivedClass :BaseClass

{

public C propertyC;

}

How could this happen:

BaseClass obj = new DerivedClass ()

I mean, the memory model of BaseClass, has no space for the newly added propertyC, so how could it still hold the value of propertyC?

On the other side, how could this can not happen:

DerivedClass obj = new BaseClass()

I thought this is the correct way since the memory model of DerivedClass has all the spaces for the BaseClass and even more. But this is not true, why?

I know I am asking a really stupid question, but could someone give me a more detail answer of this? It would be better from the perspective of the memory or compiler.

Because (and this concept is often misunderstood) the variable that holds the pointer is typed independantly from the actual concrete type of the object it points to.

So when you write

BaseClass obj = new DerivedClass ()

the part that says BaseClass obj creates a new reference variable on the Stack that the compiler understands to hold a reference to something that is, or derives, from BaseClass.

The part that reads = new DerivedClass () actually creates a new object of type DerivedClass, stores it on the Heap, and stores a pointer to that object in the memory location that obj points to. The actual object on the Heap is a DerivedClass; this is referred to as the concrete type of the object.

The variable obj is declared to be of type BaseClass. This is not a concrete type, it is just a variable type, which only restricts the compiler from storing an address into the variable that points to an object which is not a BaseClass or which does not derive from the type BaseClass.

This is done to guarantee that whatever you put into the obj variable, no matter whether it is a concrete type of BaseClass or DerivedClass, it will have all the methods, properties and other members of the type BaseClass. It tells the compiler that all uses of the obj variable should be restricted to uses of only those members of the class BaseClass.

Since BaseClass is a reference type, obj is not a BaseClass object. It is a reference to a BaseClass object. Specifically, it is a reference to the BaseClass part of the DerivedClass.

When you say this:

BaseClass obj = new DerivedClass ()

You are NOT saying "Create a container to contain this BaseClass object, and then cram this bigger DerivedClass object into it".

You are in fact creating a DerivedClass object, and it is being created in a memory space sufficient for a DerivedClass object. Never does the .NET framework lose track of the fact this this thing is specifically a DerivedClass, nor does it ever stop treating it as such.

However, when you say choose to use a BaseClass object variable, you are just creating a reference/pointer to that object that has already been created and allocated and defined and all that, and your pointer is just a little bit more vague.

It's like that guy over there on the other side of the room is a red-headed Irish slightly-overweight chicken-farmer with bad teeth and charming personality named Jimmy, but you are just referring to him as "that dude over there". The fact that you are being vague in describing him does not change what he is or any of his details, even though your vague description is entirely accurate.

Answer copied verbatim from what another user, jk, wrote on a exactly same question here on Stackoverflow.

If I tell you I have a dog, you can safely assume that I have a dog.

If I tell you I have a pet, you don't know if that animal is a dog, it

could be a cat or maybe even a giraffe. Without knowing some extra

information you can't safely assume I have a dog.

similarly a derived object is a base class object (as its a sub

class), so can be pointed to by a base class pointer. however a base

class object is not a derived class object so can't be assigned to a

derived class pointer.

(The creaking you will now hear is the analogy stretching)

Suppose you now want to buy me a gift for my pet.

In the first scenario you know it is a dog, you can buy me a leash,

everyone is happy.

In the second scenario I haven't told you what my pet is so if you are

going to buy me a gift anyway you need to know information I havent

told you (or just guess), you buy me a leash, if it turns out I really

did have a dog everyone is happy.

However if I actually had a cat then we now know you made a bad

assumption (cast) and have an unhappy cat on a leash (runtime error)

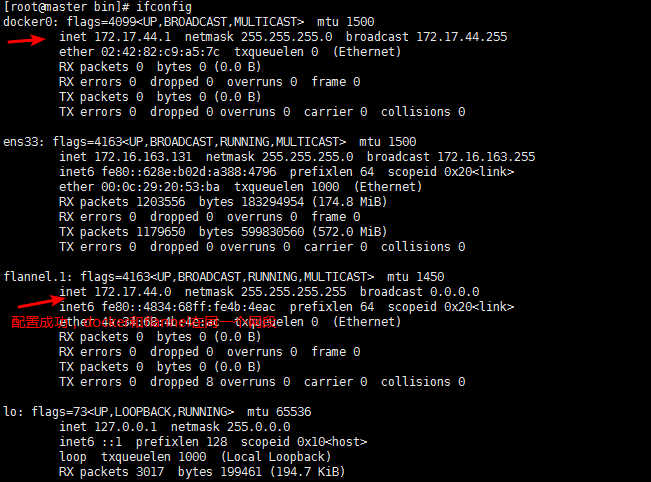

This is possible because of the way memory is allocated for base and derived classes. In a derived class, the instance variables of the base class are allocated first, followed by the instance variables of the derived class. When a base class reference variable is assigned to a derived class object, it sees the base class instance variables that it expects plus the "extra" derived class instance variables.