可以将文章内容翻译成中文,广告屏蔽插件可能会导致该功能失效(如失效,请关闭广告屏蔽插件后再试):

问题:

Being a newbie to Lisp I'm wondering if the Lisp syntax could be "fixed"?

Some people say the syntax in Lisp is one of its biggest strengths. I don't quite understand this.

Isn't it possible to replace "obvious" parentheses with a combination of white spaces, new lines and indenting? Just like in Python?

It looks to me like parentheses are the most used characters in Lisp code. I'm wondering if that's true - but if it is, isn't this a suggestion, that there is some redundancy in the syntax?

Is there some simple answer to the question - why so many parentheses?

For example:

(defun factorial (x)

(if (= x 0)

1

(* x

(factorial (- x 1)))))

Why not:

defun factorial (x)

if (= x 0)

1

* x

factorial

- x 1

e.g. close parentheses at the end of line, and always open them on new lines.

Only the 1 would be ambiguous - is it 1 or (1) - but we could introduce an exception - single tokens are not "listified".

Could this work?

Edit:

Thank you all! I see now there are some links at the lispin site.

回答1:

What you suggest appears to have been implemented in Lispin

Edit: sindikat points out in the comments below that the link is no longer valid. Here's the last valid version of the site from the Web Archive: http://wayback.archive.org/web/20080517144846id_/http://www.lispin.org/

回答2:

You'll change your mind once you write a couple of macros.

回答3:

It's been done lots of times (a < twenty line preprocessor will do wonders). But there is also an advantage to having them explicit. It drives home the parallelism between code and data, and in a way leads you out of the sort of thinking that makes you find them annoying.

You could (for an analogous example) take an object oriented language and remove all the syntactic grouping of methods into classes (so they became, in effect, overloaded functions). This would let you look at it more as you would a straight imperative language, but something would be lost as well.

When you look at lisp you're supposed to think "Everything is a list. Ommm"

(Well, Ok, the "Ommm" is optional).

回答4:

"Perhaps this process should be regarded as a rite of passage for Lisp hackers."

-- Steele and Gabriel, "The Evolution of Lisp", 1993

回答5:

Several times I've compared Lisp code and equivalent code in other languages. Lisp code has more parens, but if you count all grouping characters []{}() in other languages, Lisp has fewer parens than all these. It's not more verbose: it's more consistent!

When seen from this point of view, the "problem" is simply that Lisp uses one type of construct (lists) for everything. And this is the basis for its macros, its object system, a couple of its most powerful looping constructs, and so on. What you see as a minor style issue (would brackets look cooler? probably) is actually a sign of language power.

That said, Lisp is all about giving power to the programmer. If you want, write your own dialect that lets you do this. Lisp (unlike some languages I could mention!) is all about programmer power, so use it. If you can make it work, maybe it'll take off. I don't think it will, but there's nothing to stop you from trying, and you'll learn a lot either way.

回答6:

The point of lisp "syntax" is its non-existence. An s-expression is a tree of identities, where the tree structure is denoted by parens (and indentation). It's worth noting that sexps were meant to be a low-level representation only, but people ended up liking it more and kept using it.

What an expression means to the execution engine is incredibly flexible in lisp and it's also context sensitive.

In other languages, the level of context sensitivity is much lower and the set of building blocks you can use to build your own abstractions is much less freely extensible. Therefore, special syntax denoting the few given constructs is fitting the picture.

In lisp, I can change the meaning of everything, even in a context sensitive manner. Having special syntax for a few predefined constructs would be silly because I may end up using my own 'if', or my own specialized closures, etc.. What if my new 'if' needs 4 arguments (e.g. to group certain if's of a program and tell some groups to always fail or succeed in certain situations)? How should I extend the syntax of the predefined 'if'? It's much easier to resort to the AST (sexps), but then why bother with special syntax at all?

Also note that using an editor like emacs makes it very easy to edit such a tree in a structured way. For example, having a key to transpose two nodes in a tree is equally useful to swap variable declarations and to swap two statements in a program block (hint: that's why the "extra" parens are useful in let, cond, etc.).

So, that's the reasoning why the non-syntax of lisp is so appealing to many people who got used to the idea of extending the language instead of bending the problem to fit a predefined set of tools... but it doesn't mean that syntax sugar is not used for user-given constructs!

Some examples of user defined syntax that we use:

- cl-syntax-sugar - the most notable extension is the

[] parens used for tiny closures where you don't want to name the closure's variables

- cl-quasi-quote - most notably the

<xml > syntax to inline the xhtml generation in lisp code (please note that this syntax is provided by a user library, and it can be enabled in a context sensitive manner)

回答7:

It could work. It's called Dylan.

回答8:

Even Paul Graham, a vocal advocate for the Lisp family of languages, has removed some parentheses from his own dialect Arc:

Note to Lisp hackers: If you're used to the conventional Lisp

cond operator, this if amounts to the same thing, but with fewer

parentheses. E.g.

(cond (a b)

(c d)

(t e))

becomes

(if a b

c d

e)

(from the Arc Tutorial)

回答9:

There are two kinds of people™: those who process information by means of built-in stack machine in their brains, and those who consume it in large chunks or blocks. These groups are mutually incompatible with each other; they read different books, have different writing styles and, most importantly, write code in different programming languages. I belong to the second group; however, I know many fellow programmers from the first group.

For people in the first group, there is absolutely nothing wrong with nested clauses and subclauses; they grasp recursion naturally; they look at the code slowly, statement by statement, line by line, and stack machine in their brains keeps counting braces and parentheses at the subconscious level. Lisp syntax is quite natural to them. Hell, they probably invented stack machines and Forth language. But show them, say, Python (oh noes!), and they will glance helplessly to sheets of code, unable to understand why these stupid code blocks are left open, with no matching closing statements.

For us, poor guys in the second group, there is no other option but group code statements into blocks, and visually indent them. We look to screen filled with code, first noticing large-scale structure, then separate functions or methods, then statements groups within these methods, then lines and statements, from top to bottom. We cannot think linearly; we need visual boundaries and clean indentation policies. Hence, we cannot bend ourselves to work with Lisp; for us, it is an irregular mess of keywords and silly parentheses.

Most programming languages are compatible with both ways of thinking (those "blocks" are there for reason). Notable exceptions are Lisp and Forth, which are first group only, and Python, which is second group only. I don't think you need to adapt Lisp to your way of thinking if you belong to the second group. If you still need a functional language, try Haskell. It is a functional language designed for people who think in blocks, not stacks.

回答10:

To answer the question of why:

It's main use as far as i know is readability, so that people who look at your code can decipher it more easily.

Hope it helps.

回答11:

My personal opinion on this is: don't use newlines and indentation as "implicit" separators (I also don't like implicit grouping by operator precedence, but that is a different, although related topic).

Example: Is this valid Python? Does it do what you expect?

if foo < 0 :

bar

else :

baz

quuz

I have a little proposal: we could use a preprocessor to indent Python code automatically, by putting special characters into the code that tell it where a statement begins and ends. How about parentheses for this?

回答12:

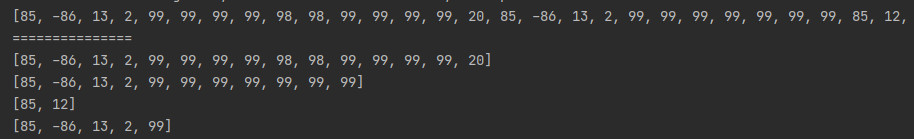

This thread is old, but I've decided to contribute, because I've created a very similar reader system.

EDIT: Some samples of usage:

!defun fact (n)

if (zerop n)

1

* n

fact

(1- n)

!defun fact !n

if !zerop n

1

!* n !fact !1- n

For more information check the homepage of project.

回答13:

Reading through the links, I found this one - Indentation-sensitive syntax - there is also Guile module, that implements this syntax, so one could directly try it.

A quite promising Lisp dialect (Arc) could be found here. (I guess one should first some real code see how it feels)

回答14:

You could take a look at Clojure. Lesser parentheses but more syntax to remember.

回答15:

I've tried out and written couple of syntaxes that rely on indentation. At the best results the whole syntax has changed it's nature and therefore the language has turned from one to another. Good indentation-based syntax isn't anything near lisp anymore.

The trouble of giving syntactic meaning for indentation doesn't rise from the idiots and \t vs. whitespace debating. Tokenizing is neither a trouble since reading newlines and spaces shouldn't be harder than anything else. The hardest thing is to determine what indentation should mean where it appears, and how to add meaning to it without making too complicated syntax for the language.

I am starting to consider original lisp style syntax is after all better when you minimize the amount of parenthesis with some clever programming. This can be done, not so easily in current lisp implementations, but in future lisp implementations it can be done easier. It's fast and simple to parse when there's only couple of rules you have to tokenize, and nearly no parsing at all.

回答16:

There is an alternate Racket Syntax.

@foo{blah blah blah}

reads as

(foo "blah blah blah")