可以将文章内容翻译成中文,广告屏蔽插件可能会导致该功能失效(如失效,请关闭广告屏蔽插件后再试):

问题:

Before you react from the gut, as I did initially, read the whole question please. I know they make you feel dirty, I know we've all been burned before and I know it's not "good style" but, are public fields ever ok?

I'm working on a fairly large scale engineering application that creates and works with an in memory model of a structure (anything from high rise building to bridge to shed, doesn't matter). There is a TON of geometric analysis and calculation involved in this project. To support this, the model is composed of many tiny immutable read-only structs to represent things like points, line segments, etc. Some of the values of these structs (like the coordinates of the points) are accessed tens or hundreds of millions of times during a typical program execution. Because of the complexity of the models and the volume of calculation, performance is absolutely critical.

I feel that we're doing everything we can to optimize our algorithms, performance test to determine bottle necks, use the right data structures, etc. etc. I don't think this is a case of premature optimization. Performance tests show order of magnitude (at least) performance boosts when accessing fields directly rather than through a property on the object. Given this information, and the fact that we can also expose the same information as properties to support data binding and other situations... is this OK? Remember, read only fields on immutable structs. Can anyone think of a reason I'm going to regret this?

Here's a sample test app:

struct Point {

public Point(double x, double y, double z) {

_x = x;

_y = y;

_z = z;

}

public readonly double _x;

public readonly double _y;

public readonly double _z;

public double X { get { return _x; } }

public double Y { get { return _y; } }

public double Z { get { return _z; } }

}

class Program {

static void Main(string[] args) {

const int loopCount = 10000000;

var point = new Point(12.0, 123.5, 0.123);

var sw = new Stopwatch();

double x, y, z;

double calculatedValue;

sw.Start();

for (int i = 0; i < loopCount; i++) {

x = point._x;

y = point._y;

z = point._z;

calculatedValue = point._x * point._y / point._z;

}

sw.Stop();

double fieldTime = sw.ElapsedMilliseconds;

Console.WriteLine("Direct field access: " + fieldTime);

sw.Reset();

sw.Start();

for (int i = 0; i < loopCount; i++) {

x = point.X;

y = point.Y;

z = point.Z;

calculatedValue = point.X * point.Y / point.Z;

}

sw.Stop();

double propertyTime = sw.ElapsedMilliseconds;

Console.WriteLine("Property access: " + propertyTime);

double totalDiff = propertyTime - fieldTime;

Console.WriteLine("Total difference: " + totalDiff);

double averageDiff = totalDiff / loopCount;

Console.WriteLine("Average difference: " + averageDiff);

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

result:

Direct field access: 3262

Property access: 24248

Total difference: 20986

Average difference: 0.00020986

It's only 21 seconds, but why not?

回答1:

Your test isn't really being fair to the property-based versions. The JIT is smart enough to inline simple properties so that they have a runtime performance equivalent to that of direct field access, but it doesn't seem smart enough (today) to detect when the properties access constant values.

In your example, the entire loop body of the field access version is optimized away, becoming just:

for (int i = 0; i < loopCount; i++)

00000025 xor eax,eax

00000027 inc eax

00000028 cmp eax,989680h

0000002d jl 00000027

}

whereas the second version, is actually performing the floating point division on each iteration:

for (int i = 0; i < loopCount; i++)

00000094 xor eax,eax

00000096 fld dword ptr ds:[01300210h]

0000009c fdiv qword ptr ds:[01300218h]

000000a2 fstp st(0)

000000a4 inc eax

000000a5 cmp eax,989680h

000000aa jl 00000096

}

Making just two small changes to your application to make it more realistic makes the two operations practically identical in performance.

First, randomize the input values so that they aren't constants and the JIT isn't smart enough to remove the division entirely.

Change from:

Point point = new Point(12.0, 123.5, 0.123);

to:

Random r = new Random();

Point point = new Point(r.NextDouble(), r.NextDouble(), r.NextDouble());

Secondly, ensure that the results of each loop iteration are used somewhere:

Before each loop, set calculatedValue = 0 so they both start at the same point. After each loop call Console.WriteLine(calculatedValue.ToString()) to make sure that the result is "used" so the compiler doesn't optimize it away. Finally, change the body of the loop from "calculatedValue = ..." to "calculatedValue += ..." so that each iteration is used.

On my machine, these changes (with a release build) yield the following results:

Direct field access: 133

Property access: 133

Total difference: 0

Average difference: 0

Just as we expect, the x86 for each of these modified loops is identical (except for the loop address)

000000dd xor eax,eax

000000df fld qword ptr [esp+20h]

000000e3 fmul qword ptr [esp+28h]

000000e7 fdiv qword ptr [esp+30h]

000000eb fstp st(0)

000000ed inc eax

000000ee cmp eax,989680h

000000f3 jl 000000DF (This loop address is the only difference)

回答2:

Given that you deal with immutable objects with readonly fields, I would say that you have hit the one case when I don't find public fields to be a dirty habit.

回答3:

IMO, the "no public fields" rule is one of those rules which are technically correct, but unless you are designing a library intended to be used by the public it is unlikely to cause you any problem if you break it.

Before I get too massively downvoted, I should add that encapsulation is a good thing. Given the invariant "the Value property must be null if HasValue is false", this design is flawed:

class A {

public bool HasValue;

public object Value;

}

However, given that invariant, this design is equally flawed:

class A {

public bool HasValue { get; set; }

public object Value { get; set; }

}

The correct design is

class A {

public bool HasValue { get; private set; }

public object Value { get; private set; }

public void SetValue(bool hasValue, object value) {

if (!hasValue && value != null)

throw new ArgumentException();

this.HasValue = hasValue;

this.Value = value;

}

}

(and even better would be to provide an initializing constructor and make the class immutable).

回答4:

I know you feel kind of dirty doing this, but it isn't uncommon for rules and guidelines to get shot to hell when performance becomes an issue. For example, quite a few high traffic websites using MySQL have data duplication and denormalized tables. Others go even crazier.

Moral of the story - it may go against everything you were taught or advised, but the benchmarks don't lie. If it works better, just do it.

回答5:

If you really need that extra performance, then it's probably the right thing to do. If you don't need the extra performance then it's probably not.

Rico Mariani has a couple of related posts:

- Ten Questions on Value-Based Programming

- Ten Questions on Value-Based Programming : Solution

回答6:

Personally, the only time I would consider using public fields is in a very implementation-specific private nested class.

Other times it just feels too "wrong" to do it.

The CLR will take care of performance by optimising out the method/property (in release builds) so that shouldn't be an issue.

回答7:

Not that I disagree with the other answers, or with your conclusion... but I'd like to know where you get the order of magnitude performance difference stat from. As I understand the C# compiler, any simple property (with no additional code other than direct access to the field), should get inlined by the JIT compiler as a direct access anyway.

The advantedge of using properties even in these simple cases (in most situations) was that by writing it as a property you allow for future changes that might modify the property. (Although in your case there would not be any such changes in future of course)

回答8:

Try compiling a release build and running directly from the exe instead of through the debugger. If the application was run through a debugger then the JIT compiler will not inline the property accessors. I was not able to replicate your results. In fact, each test I ran indicated that there was virtually no difference in execution time.

But, like the others I am not completely oppossed to direct field access. Especially because it is easy to make the field private and add a public property accessor at a later time without needed make any more code modifications to get the application to compile.

Edit: Okay, my initial tests used an int data type instead of double. I see a huge difference when using doubles. With ints the direct vs. property is virtually the same. With doubles property access is about 7x slower than direct access on my machine. This is somewhat puzzling to me.

Also, it is important to run the tests outside of the debugger. Even in release builds the debugger adds overhead which skews the results.

回答9:

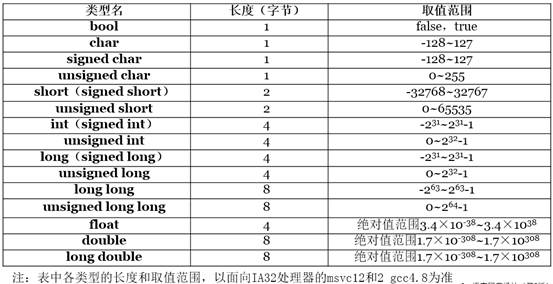

Here's some scenarios where it is OK (from the Framework Design Guidelines book):

- DO use constant fields for constants

that will never change.

- DO use public

static readonly fields for predefined

object instances.

And where it is not:

- DO NOT assign instances of mutable

types to readonly fields.

From what you have stated I don't get why your trivial properties don't get inlined by the JIT?

回答10:

If you modify your test to use the temp variables you assign rather than directly access the properties in your calculation you will see a large performance improvement:

sw.Start();

for (int i = 0; i < loopCount; i++)

{

x = point._x;

y = point._y;

z = point._z;

calculatedValue = x * y / z;

}

sw.Stop();

double fieldTime = sw.ElapsedMilliseconds;

Console.WriteLine("Direct field access: " + fieldTime);

sw.Reset();

sw.Start();

for (int i = 0; i < loopCount; i++)

{

x = point.X;

y = point.Y;

z = point.Z;

calculatedValue = x * y / z;

}

sw.Stop();

回答11:

Perhaps I'll repeat someone else, but here's my point too if it may help.

Teachings are to give you the tools you need to achieve a certain level of ease when encountering such situations.

The Agile Software development methodology says that you have to first deliver the product to your client no matter what your code might look like. Second, you may optimize and make your code "beautiful" or according to the programming states of the art.

Here, either you or your client require performance. Within your project, PERFORMANCE is CRUCIAL, if I understand correctly.

So, I guess you'll agree with me that we don't care about what the code might look like or whether it respects the "art". Do what you have to to make it performant and powerful! Properties allow your code to "format" the data I/O if required. A property has its own memory address, then it looks for its member address when you return the member's value, so you got two searches of address. If performance is such critical, just do it, and make your immutable members public. :-)

This reflects some others point of view too, if I read correctly. :)

Have a good day!

回答12:

Types which encapsulate functionality should use properties. Types which only serve to hold data should use public fields, except in the case of immutable classes (where wrapping fields in read-only properties is the only way to reliably protect them against modification). Exposing members as public fields essentially proclaims "these members may be freely modified at any time without regard for anything else". If the type in question is a class type, it further proclaims "anyone who exposes a reference to this thing will be allowing the recipient to change these members at any time in any fashion they see fit." While one shouldn't expose public fields in cases where such a proclamation would be inappropriate, one should expose public fields in cases where such a proclamation would be appropriate and client code could benefit from the assumptions enabled thereby.