int func(char* str)

{

char buffer[100];

unsigned short len = strlen(str);

if(len >= 100)

{

return (-1);

}

strncpy(buffer,str,strlen(str));

return 0;

}

This code is vulnerable to a buffer overflow attack, and I'm trying to figure out why. I'm thinking it has to do with len being declared a short instead of an int, but I'm not really sure.

Any ideas?

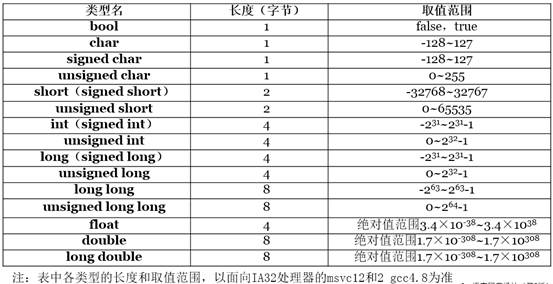

On most compilers the maximum value of an unsigned short is 65535.

Any value above that gets wrapped around, so 65536 becomes 0, and 65600 becomes 65.

This means that long strings of the right length (e.g. 65600) will pass the check, and overflow the buffer.

Use size_t to store the result of strlen(), not unsigned short, and compare len to an expression that directly encodes the size of buffer. So for example:

char buffer[100];

size_t len = strlen(str);

if (len >= sizeof(buffer) / sizeof(buffer[0])) return -1;

memcpy(buffer, str, len + 1);

The problem is here:

strncpy(buffer,str,strlen(str));

^^^^^^^^^^^

If the string is greater than the length of the target buffer, strncpy will still copy it over. You are basing the number of characters of the string as the number to copy instead of the size of the buffer. The correct way to do this is as follows:

strncpy(buffer,str, sizeof(buff) - 1);

buffer[sizeof(buff) - 1] = '\0';

What this does is limit the amount of data copied to the actual size of the buffer minus one for the null terminating character. Then we set the last byte in the buffer to the null character as an added safeguard. The reason for this is because strncpy will copy upto n bytes, including the terminating null, if strlen(str) < len - 1. If not, then the null is not copied and you have a crash scenario because now your buffer has a unterminated string.

Hope this helps.

EDIT: Upon further examination and input from others, a possible coding for the function follows:

int func (char *str)

{

char buffer[100];

unsigned short size = sizeof(buffer);

unsigned short len = strlen(str);

if (len > size - 1) return(-1);

memcpy(buffer, str, len + 1);

buffer[size - 1] = '\0';

return(0);

}

Since we already know the length of the string, we can use memcpy to copy the string from the location that is referenced by str into the buffer. Note that per the manual page for strlen(3) (on a FreeBSD 9.3 system), the following is stated:

The strlen() function returns the number of characters that precede the

terminating NUL character. The strnlen() function returns either the

same result as strlen() or maxlen, whichever is smaller.

Which I interpret to be that the length of the string does not include the null. That is why I copy len + 1 bytes to include the null, and the test checks to make sure that the length < size of buffer - 2. Minus one because the buffer starts at position 0, and minus another one to make sure there's room for the null.

EDIT: Turns out, the size of something starts with 1 while access starts with 0, so the -2 before was incorrect because it would return an error for anything > 98 bytes but it should be > 99 bytes.

EDIT: Although the answer about a unsigned short is generally correct as the maximum length that can be represented is 65,535 characters, it doesn't really matter because if the string is longer than that, the value will wrap around. It's like taking 75,231 (which is 0x000125DF) and masking off the top 16 bits giving you 9695 (0x000025DF). The only problem that I see with this is the first 100 chars past 65,535 as the length check will allow the copy, but it will only copy up to the first 100 characters of the string in all cases and null terminate the string. So even with the wraparound issue, the buffer still will not be overflowed.

This may or may not in itself pose a security risk depending on the content of the string and what you are using it for. If it's just straight text that is human readable, then there is generally no problem. You just get a truncated string. However, if it's something like a URL or even a SQL command sequence, you could have a problem.

Even though you're using strncpy, the length of the cutoff is still dependent on the passed string pointer. You have no idea how long that string is (the location of the null terminator relative to the pointer, that is). So calling strlen alone opens you up to vulnerability. If you want to be more secure, use strnlen(str, 100).

Full code corrected would be:

int func(char *str) {

char buffer[100];

unsigned short len = strnlen(str, 100); // sizeof buffer

if (len >= 100) {

return -1;

}

strcpy(buffer, str); // this is safe since null terminator is less than 100th index

return 0;

}

The answer with the wrapping is right. But there is a problem I think was not mentioned

if(len >= 100)

Well if Len would be 100 we'd copy 100 elements an we'd not have trailing \0. That clearly would mean any other function depending on proper ended string would walk way beyond the original array.

The string problematic from C is IMHO unsolvable. You'd alway better have some limits before the call, but even that won't help. There is no bounds checking and so buffer overflows always can and unfortunately will happen....

Beyond the security issues involved with calling strlen more than once, one should generally not use string methods on strings whose length is precisely known [for most string functions, there's only a really narrow case where they should be used--on strings for which a maximum length can be guaranteed, but the precise length isn't known]. Once the length of the input string is known and the length of the output buffer is known, one should figure out how big a region should be copied and then use memcpy() to actually perform the copy in question. Although it's possible that strcpy might outperform memcpy() when copying a string of only 1-3 bytes or so, on many platforms memcpy() is likely to be more than twice as fast when dealing with larger strings.

Although there are some situations where security would come at the cost of performance, this is a situation where the secure approach is also the faster one. In some cases, it may be reasonable to write code which is not secure against weirdly-behaving inputs, if code supplying the inputs can ensure they will be well-behaved, and if guarding against ill-behaved inputs would impede performance. Ensuring that string lengths are only checked once improves both performance and security, though one extra thing can be done to help guard security even when tracking string length manually: for every string which is expected to have a trailing null, write the trailing null explicitly rather than expecting the source string to have it. Thus, if one were writing an strdup equivalent:

char *strdupe(char const *src)

{

size_t len = strlen(src);

char *dest = malloc(len+1);

// Calculation can't wrap if string is in valid-size memory block

if (!dest) return (OUT_OF_MEMORY(),(char*)0);

// OUT_OF_MEMORY is expected to halt; the return guards if it doesn't

memcpy(dest, src, len);

dest[len]=0;

return dest;

}

Note that the last statement could generally be omitted if the memcpy had processed len+1 bytes, but it another thread were to modify the source string the result could be a non-NUL-terminated destination string.