This question already has an answer here:

-

Comparing Integer values in Java, strange behavior

3 answers

Integer comparison in Java is tricky, in that int and Integer behave differently. I get that part.

But, as this example program shows, (Integer)400 (line #4) behaves differently than (Integer)5 (line #3). Why is this??

import java.util.*;

import java.lang.*;

import java.io.*;

class Ideone

{

public static void main (String[] args) throws java.lang.Exception

{

System.out.format("1. 5 == 5 : %b\n", 5 == 5);

System.out.format("2. (int)5 == (int)5 : %b\n", (int)5 == (int)5);

System.out.format("3. (Integer)5 == (Integer)5 : %b\n", (Integer)5 == (Integer)5);

System.out.format("4. (Integer)400 == (Integer)400 : %b\n", (Integer)400 == (Integer)400);

System.out.format("5. new Integer(5) == (Integer)5 : %b\n", new Integer(5) == (Integer)5);

}

}

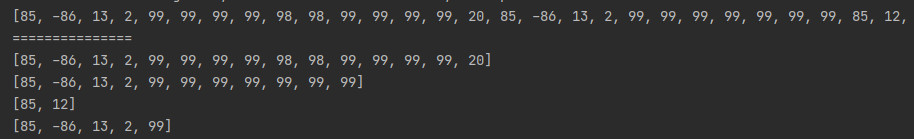

Result

1. 5 == 5 : true // Expected

2. (int)5 == (int)5 : true // Expected

3. (Integer)5 == (Integer)5 : true // Expected

4. (Integer)400 == (Integer)400 : false // WHAT?

5. new Integer(5) == (Integer)5 : false // Odd, but expected

From the JLS

If the value p being boxed is true, false, a byte, or a char in the range \u0000 to \u007f, or an int or short number between -128 and 127 (inclusive), then let r1 and r2 be the results of any two boxing conversions of p. It is always the case that r1 == r2.

Ideally, boxing a given primitive value p, would always yield an identical reference. In practice, this may not be feasible using existing implementation techniques. The rules above are a pragmatic compromise. The final clause above requires that certain common values always be boxed into indistinguishable objects. The implementation may cache these, lazily or eagerly. For other values, this formulation disallows any assumptions about the identity of the boxed values on the programmer's part. This would allow (but not require) sharing of some or all of these references.

This ensures that in most common cases, the behavior will be the desired one, without imposing an undue performance penalty, especially on small devices. Less memory-limited implementations might, for example, cache all char and short values, as well as int and long values in the range of -32K to +32K.

Because in autoboxing a literal to Integer , are evaluated as following:

(Integer)400 --- Integer.valueOf(400)

valueOf is implemented such that certain numbers are "pooled", and it returns the same instance for values smaller than 128.

And since (Integer)5 is less than 128, it would be pooled and (Integer)400won't be pooled.

Therefore:

3. (Integer)5 == (Integer)5 : true // Expected -- since 5 is pooled (i.e same reference)

and

4. Integer(400) == (Integer)400 : false // WHAT? -- since 400 is not pooled (i.e different reference)

Here is a quote from JLS:

If the value p being boxed is true, false, a byte, or a char in the range \u0000 to \u007f, or an int or short number between -128 and 127 (inclusive), then let r1 and r2 be the results of any two boxing conversions of p. It is always the case that r1 == r2.

In short Integer uses pool, so for numbers from -128 to 127 you will get always the same object after boxing, and for example new Integer(120) == new Integer(120) will evaluate to true, but new Integer(130) == new Integer(130) will evaluate to false.