Let's consider the following Prolog program (from "The Art of Prolog"):

natural_number(0).

natural_number(s(X)) :- natural_number(X).

plus(X, 0, X) :- natural_number(X).

plus(X, s(Y), s(Z)) :- plus(X, Y, Z).

and the query:

?- plus(s(s(s(0))), s(0), Z).

Both SICStus and SWI produce the expected Z = s(s(s(s(0)))) answer, but query the user for the next answer (a correct no/false answer). However, I cannot understand why there is an open branch in the SLD tree after the only goal is found. I tried debugging both under SICStus and under SWI, but I am not really able to interpret the result yet. I can only say that, as far as I could understand, both backtrack to plus(s(s(s(0))), 0, _Z2). Can someone help me understanding this behavior?

The problem is not directly related to SLD trees, since Prolog

systems do not build SLD trees in a look-ahead manner as

you describe it. But some optimizations found in certain Prolog

systems essentially have this effect and change the blind brute

force head matching. Namely indexing and choice point elimination.

There is now a known limitation of SWI-Prolog. Although it does

multi-argument indexing, it does not do choice point elimination

for non-first argument indexes cascaded indexing. Means

it only picks one argument, but then no further. There are some

Prolog systems that do multi argument indexing and cascaded indexing.

For example in Jekejeke Prolog we do not have No/false:

Bye

P.S.: The newest version of Jekejeke Prolog even does not

literally cascade, since it detects that the first argument index

has no sensitivity. Therefore although it builds the index for

the first argument due to the actual call pattern, it skips the

first argument index and does not use it, and solely uses the

second argument. Skipping gives a little speed. :-)

The skipping is seen via the dump/1 command of the

development environment version:

?- dump(plus/3).

-------- plus/3 ---------

length=2

arg=0

=length=2

arg=1

0=length=1

s=length=1

Yes

So it has not decended into arg=0 and built an arg=1

index there, but instead built in parallel an arg=0 and

an arg=1 index. We might still call this heuristic cascading

since individual queries lead to multiple indexes, but they

have not really the shape of a cascade.

Many Prolog systems are not as smart as we expect them to be. This has several reasons, mostly because of a tradeoff choice of the implementer. What appears important to some might not be that important to others.

As a consequence these leftover choicepoints may accumulate in time and prevent to free auxiliary data. For example, when you want to read in a long list of text. A list that is that long that it does not fit into memory at once, but still can be processed efficiently with library(pio).

If you expect exactly one answer, you might use call_semidet/1 to make it determinate.

See this answer for its definition and a use case.

?- plus(s(s(s(0))), s(0), Z).

Z = s(s(s(s(0)))) ;

false.

?- call_semidet(plus(s(s(s(0))), s(0), Z)).

Z = s(s(s(s(0)))).

But you can see it also from a more optimistic side: Modern toplevels (like the one in SWI) do show you when there are leftover choicepoints. So you can consider some countermeasures like call_semidet/1.

Here are some related answers:

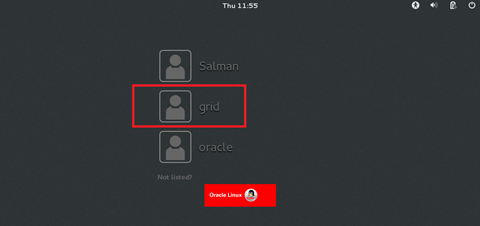

To us, it's apparent that the two clauses for plus are 'disjunctive'. We can say that because we know that 0 \= s(Y). But (I think) such analysis in general is prohibitive, and Prolog then consider such branch still to be proved: here a trace showing that the call (7) is still 'open' for alternatives after the first solution has been found.