I have a quick question regarding the clone() method in Java, used as super.clone() in regard to inheritance - where I call the clone() method in the parent class all the way up from the button.

The clone() method is supposed to return a copy of this object, however if I have three classes in an inheritance heirachy and call super.clone() three times, why doesn't the highest class in the inheritance heirachy, just under class Object, get a copy of that class returned?

Suppose we have three classes: A, B and C, where A -> B -> C (inherit = ->)

Then calling super.clone() in class C, invokes clone() in B which calls super.clone(), invoke clone() in A which call super.clone() 'this time Object.clone() gets called'. Why is it not a copy of the this object with respect to class A that gets returned from Object.clone()? That sounds logical to me.

It sounds like there are at least two problems at work here:

It sounds like you're confused about how clone() normally gets implemented.

It sounds like you're thinking that cloning is a good idea (vs. using a copy constructor, factories or their equivalent).

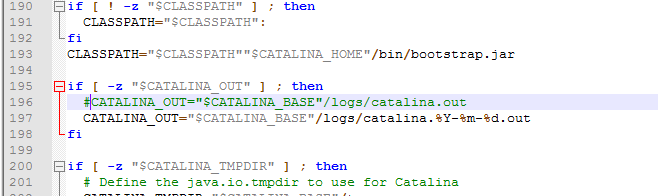

Here is an example of an implementation of a clone method:

@Override

public Object clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException {

//get initial bit-by-bit copy, which handles all immutable fields

Fruit result = (Fruit)super.clone();

//mutable fields need to be made independent of this object, for reasons

//similar to those for defensive copies - to prevent unwanted access to

//this object's internal state

result.fBestBeforeDate = new Date( this.fBestBeforeDate.getTime() );

return result;

}

Note that the result of super.clone() is immediately cast to a Fruit. That allows the inheriting method to then modify the Fruit-specific member data (fBestBeforeDate in this case).

Thus, the call to a child clone() method, while it will call the parents' clones, also adds its own specific modifications to the newly made copy. What comes out, in this case, will be a Fruit, not an Object.

Now, more importantly, cloning is a bad idea. Copy constructors and factories provide much more intuitive and easily maintained alternatives. Try reading the header on the Java Practices link that I attached to the example: that summarizes some of the problems. Josh Bloch also has a much longer discussion: cloning should definitely be avoided. Here is an excellent summary paragraph on why he thinks cloning is a problem:

Object's clone method is very tricky. It's based on field copies, and

it's "extra-linguistic." It creates an object without calling a

constructor. There are no guarantees that it preserves the invariants

established by the constructors. There have been lots of bugs over the

years, both in and outside Sun, stemming from the fact that if you

just call super.clone repeatedly up the chain until you have cloned an

object, you have a shallow copy of the object. The clone generally

shares state with the object being cloned. If that state is mutable,

you don't have two independent objects. If you modify one, the other

changes as well. And all of a sudden, you get random behavior.

Although one answer is accepted, I do not think it fully answers the first part of the question (why downcasting in subclasses always works).

Although I cannot really explain it, I think I can clear up some of the poster's confusion which was the same as mine.

We have the following classes

class A implements Cloneable

{

@Override

protected A clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException // could be public

{

Object clone = super.clone();

System.out.println("Class A: " + clone.getClass()); // will print 'C'

return (A) clone;

}

}

class B extends A

{

@Override

protected B clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException

{

A clone = super.clone();

System.out.println("Class B: " + clone.getClass()); // will print 'C'

return (B) clone;

}

}

class C extends B

{

@Override

protected C clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException

{

B clone = super.clone();

System.out.println("Class C: " + clone.getClass()); // will print 'C'

return (C) clone;

}

}

static main(char[] argv)

{

C c = new C();

C cloned_c = c.clone();

}

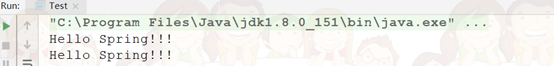

The result of this is that

Class A: C

Class B: C

Class C: C

is printed on the command line.

So, as a matter of fact, the clone()method of Object somehow can look down the call stack and see which type of object at the start of the chain invoked clone(), then, provided the calls bubble up so that Object#clone()is actually called, an object of that type is created. So this happens already in class C, which is strange, but it explains why the downcasts do not result in a ClassCastException. I've checked with the OpenJDK, and it appears this comes by some Java black magic implemented in native code.

Its a special native method. This was done to make cloning easier. Otherwise you will have to copy the whole code of your ancestor classes.

If clone() in B returns whatever clone() in A returns and clone() in C returns whatever the clone() in B returns then clone() in C will return whatever the clone() in A returns.

this class has information about this class as well as it is associated with another class. So, conceptually this class's object will have information of associated class as well. this object is incomplete object without associated object/parent class.all direct as well as indirect fields in this class needs to be copied make it a worth it new clone of current object. we cannot access only that portion of reference which only denotes child section.