Let’s consider this very short snippet of code:

#include <stdlib.h>

int main()

{

char* a = malloc(20000);

char* b = realloc(a, 5);

free(b);

return 0;

}

After reading the man page for realloc, I was not entirely sure that the second line would cause the 19995 extra bytes to be freed. To quote the man page: The realloc() function changes the size of the memory block pointed to by ptr to size bytes., but from that definition, can I be sure the rest will be freed?

I mean, the block pointed by b certainly contains 5 free bytes, so would it be enough for a lazy complying allocator to just not do anything for the realloc line?

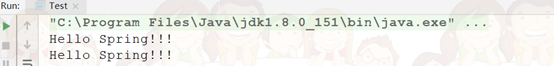

Note: The allocator I use seems to free the 19 995 extra bytes, as shown by valgrind when commenting out the free(b) line :

==4457== HEAP SUMMARY:

==4457== in use at exit: 5 bytes in 1 blocks

==4457== total heap usage: 2 allocs, 1 frees, 20,005 bytes allocated

Yes, guaranteed by the C Standard if the new object can be allocated.

(C99, 7.20.3.4p2) "The realloc function deallocates the old object pointed to by ptr and returns a pointer to a new object that has the size specified by size."

Yes—if it succeeds.

Your code snippet shows a well-known, nefarious bug:

char* b = (char*) realloc(a, 5);

If this succeeds, the memory that was previously allocated to a will be freed, and b will point to 5 bytes of memory that may or may not overlap the original block.

However, if the call fails, b will benull, but a will still point to its original memory, which will still be valid. In that case, you need to free(a) in order to release the memory.

It's even worse if you use the common (dangerous) idiom:

a = realloc(a, NEW_SIZE); // Don't do this!

If the call to realloc fails, a will be null and its original memory will be orphaned, making it irretrievably lost until your program exits.

This depends on your libc implementation. All of the following is conformant behaviour:

- doing nothing, ie letting the data remain where it is and returning the old block, possibly re-using the now unused bytes for further allocations

(afaik such re-use is not common)

- copying the data to a new block and releasing the old one back to the OS

- copying the data to a new block and retaining the old one for further allocations

It's also possible to

- return a null pointer if a new block can't be allocated

In this case, the old data will also remain where it is, which can lead to memory leaks, eg if the return value of realloc() overwrites the only copy of the pointer to that block.

A sensible libc implementation will use some heuristic to determine which solution is most efficient.

Also keep in mind that this description is at implementation level: Semantically, realloc() always frees the object as long as allocation doesn't fail.

The realloc function has the following contract:

void* result = realloc(ptr, new_size)

- If result is NULL, then ptr is still valid and unchanged.

- If result is non-NULL, then ptr is now invalid (as if it had been freed) and must not ever be used again. result is now a pointer to exactly new_size bytes of data.

The precise details of what goes on under the hood are implementation-specific - for example result may be equal to ptr (but additional space beyond new_size must not be touched anymore) and realloc may call free, or may do its own internal free representation. The key thing is that as a developer you no longer have responsibility for ptr if realloc returns non-null, and you do still have responsibility for it if realloc returns NULL.

It seems unlikely that 19995 bytes were freed.

What's more likely is that realloc replaced the 20000-byte block by another 5-byte block,

that is, the 20000-byte block was freed and a new 5-byte block was allocated.