I've always set up metaclasses something like this:

class SomeMetaClass(type):

def __new__(cls, name, bases, dict):

#do stuff here

But I just came across a metaclass that was defined like this:

class SomeMetaClass(type):

def __init__(self, name, bases, dict):

#do stuff here

Is there any reason to prefer one over the other?

Update: Bear in mind that I'm asking about using __new__ and __init__ in a metaclass. I already understand the difference between them in another class. But in a metaclass, I can't use __new__ to implement caching because __new__ is only called upon class creation in a metaclass.

If you want to alter the attributes dict before the class is created, or change the bases tuple, you have to use __new__. By the time __init__ sees the arguments, the class object already exists. Also, you have to use __new__ if you want to return something other than a newly created class of the type in question.

On the other hand, by the time __init__ runs, the class does exist. Thus, you can do things like give a reference to the just-created class to one of its member objects.

Edit: changed wording to make it more clear that by "object", I mean class-object.

You can see the full writeup in the official docs, but basically, __new__ is called before the new object is created (for the purpose of creating it) and __init__ is called after the new object is created (for the purpose of initializing it).

Using __new__ allows tricks like object caching (always returning the same object for the same arguments rather than creating new ones) or producing objects of a different class than requested (sometimes used to return more-specific subclasses of the requested class). Generally, unless you're doing something pretty odd, __new__ is of limited utility. If you don't need to invoke such trickery, stick with __init__.

You can implement caching. Person("Jack") always returns a new object in the second example while you can lookup an existing instance in the first example with __new__ (or not return anything if you want).

As has been said, if you intend to alter something like the base classes or the attributes, you’ll have to do it in __new__. The same is true for the name of the class but there seems to be a peculiarity with it. When you change name, it is not propagated to __init__, even though, for example attr is.

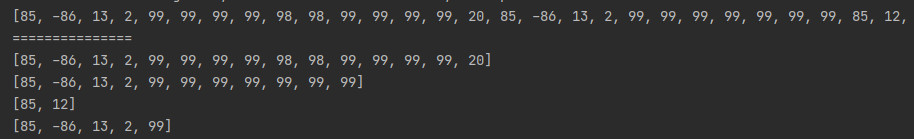

So you’ll have:

class Meta(type):

def __new__(cls, name, bases, attr):

name = "A_class_named_" + name

return type.__new__(cls, name, bases, attr)

def __init__(cls, name, bases, attr):

print "I am still called '" + name + "' in init"

return super(Meta, cls).__init__(name, bases, attr)

class A(object):

__metaclass__ = Meta

print "Now I'm", A.__name__

prints

I am still called 'A' in init

Now I'm A_class_named_A

This is important to know, if __init__ calls a super metaclass which does some additional magic. In that case, one has to change the name again before calling super.__init__.