可以将文章内容翻译成中文,广告屏蔽插件可能会导致该功能失效(如失效,请关闭广告屏蔽插件后再试):

问题:

On more than one occasion I've been asked to implement rules for password selection for software I'm developing. Typical suggestions include things like:

- Passwords must be at least N characters long;

- Passwords must include lowercase, uppercase and numbers;

- No reuse of the last M passwords (or passwords used within P days).

And so on.

Something has always bugged me about putting any restrictions on passwords though - by restricting the available passwords, you reduce the size of the space of all allowable passwords. Doesn't this make passwords easier to guess?

Equally, by making users create complex, frequently-changing passwords, the temptation to write them down increases, also reducing security.

Is there any quantitative evidence that password restriction rules make systems more secure?

If there is, what are the 'most secure' password restriction strategies to use?

Edit Ólafur Waage has kindly pointed out a Coding Horror article on dictionary attacks which has a lot of useful analysis in it, but it strikes me that dictionary attacks can be massively reduced (as Jeff suggests) by simply adding a delay following a failed authentication attempt.

With this in mind, what evidence is there that forced-complex passwords are more secure?

回答1:

Something has always bugged me about

putting any restrictions on passwords

though - by restricting the available

passwords, you reduce the size of the

space of all allowable passwords.

Doesn't this make passwords easier to

guess?

In theory, yes. In practice, the "weak" passwords you disallow represent a tiny subset of all possible passwords that is disproportionately often chosen when there are no restrictions, and which attackers know to attack first.

Equally, by making users create

complex, frequently-changing

passwords, the temptation to write

them down increases, also reducing

security.

Correct. Forcing users to change passwords every month is a very, very bad idea, except perhaps in extreme high-security environments where everyone really understands the need for security.

回答2:

Those kind of rules definitely help because it stops stupid users from using passwords like "mypassword", which unfortunately happens quite often.

So actually, you are forcing the users into an extremely large set of potential passwords. It doesn't matter that you are excluding the set of all passwords with only lowercase letters, because the remaining set is still orders of magnitude larger.

BUT my big pet peeves are password restrictions I've encountered on major sites, like

- No special characters

- Maximum length

Why would anyone do this? W.H.Y.????

回答3:

A nice read up on this is Jeff's article on Dictionary Attacks.

回答4:

- Never prevent the user from doing what they really want, unless there is a technical limitation from doing so.

- You may nag the hell out of the user for doing stupid things like using a dictionary word or a 3-character password, or only using numbers, but see #1 above.

- There is no good technical reason to require only alphanumerics, or at least one capital letter, or at least one number; see #1 above.

I forget which website had this advice regarding passwords: "Pick a password that is very easy for you to remember, but very hard for someone else to guess." But then they proceeded to require at least one capital letter and one number.

The problem with passwords is that they are so ubiquitous that it is essentially impossible for any person without a photographic memory to actually remember them without writing them down, and therefore leaving a serious security hole should someone gain access to this list of written-down passwords.

The only way I am able to manage this for myself is to split most of my passwords -- and I just checked my list, I'm up to 130 so far! -- into two parts, one which is the same in all cases, and the other which is unique but simple. (I break this rule for sites requiring high-security like bank accounts.)

By requiring "complexity" as defined as multiple types of characters all present, is that it forces people into a disparate set of conventions for different sites, which makes it harder to remember the password in question.

The only reason I will acknowledge for sites limiting the set of allowable password characters, is that it needs to be typeable on a keyboard. If you have to assume the account needs to be accessed from multiple countries, then keyboards may not always support the same characters on the user's home keyboard.

One of these days I'll have to make a blog posting on the subject. :(

回答5:

My old limit theorem:

As the security of the password approaches adequate, the probability that it will be on a sticky note attached to the computer or monitor approaches one.

回答6:

One also might point out the recent fiasco over at twitter where one of their admin's password turned out to be "happiness", which fell to a dictionary attack.

回答7:

For questions like this, I ask myself what Bruce Schneier would do - the linked article is about how to choose passwords which are hard to guess with typical attacks.

Also note that if you add a delay after a failed attempt, you might also want to add a delay after a successful attempt, otherwise the delay is simply a signal that the attack has failed an other attempt should be launched.

回答8:

Whilst this does not directly answer your question, I personally find the most aggrevating rule I have encountered one whereby you could not reuse any password previously used. After working at the same place for a number of years, and having to change your password every 2/3 months, the ability to use a password I chose over a year ago would not seem to be particularly unsafe or unsecure. If I have used "safe" passwords in the past (Alphanumeric with changes in case), surely reusing them after a perios of say a year or 2 (depending on how regularly you have to change your password) would seem to be acceptable to me. It also means I am less likely to use "easier" passwords, which might happen if I can't think of anything easy to remember and difficult to guess!

回答9:

First let me say that details such as minimum length, case sensitivity and required special characters should depend on who has access and what the password allows them to do. If it's a code to launch a nuclear missile, it should be more strict than a password to log in to play your paid online edition of Angry Birds.

But I've got a SPECIFIC beef with case sensitivity.

For starters, users hate it. The human brain thinks "A=a". Of course, developers brains' aren't usually typical. ;-) But developers are also inconvenienced by case sensitivity.

Second, the CapsLock key is too easy to hit by mistake. It's right between Tab and Shift keys, but it SHOULD be up above the Esc key. Its location was established long ago in the days of typewriters, which had no alternate font available. In those days it was useful to have it there.

All passwords have risk... You're balancing risk with ease-of-use, and yes, usability matters.

MY ARGUMENT:

Yes, case sensitivity is more secure for a given password length. But unless someone is making me do otherwise, I opt for a longer minimum password length. Even if we assume only letters and digits are allowed, each added character multiplies number of the possible passwords by 36.

Someone who's less lazy than me with math could tell you the difference in number of combinations between, say a minimum 8-character case-sensitive password, and a 12-character case-insensitive password. I think most users would prefer the latter.

Also, not all apps expose usernames to others, so there are potentially two fields the hacker may have to find.

I also prefer to allow spaces in passwords as long as the majority of the password isn't spaces.

In the project I'm developing now, my management screen allows the administrator to change password requirements, which apply to all future passwords. He can also force all users to update passwords (to new requirements) at any time after next logon. I do this because I feel my stuff doesn't need case-sensitivity, but the administrator (who probably paid me for the software) may disagree so I let that person decide.

The PIN for my bank card is only four digits. Since it's only numbers it's not case sensitive. And heck, it's my MONEY! If you consider nothing else, this sounds pretty insecure, were it not for the fact that the hacker has to steal my card to get my money. (And have his photo taken.)

One other beef: Developers who come onto StackOverflow and regurgitate hard-and-fast rules that they read in an article somewhere. "Never hard code anything." (As if that's possible.) "All queries must be parameterized" (not if the the user doesn't contribute to the query.) etc.

Please excuse the rant. ;-) I promise I respect disagreement.

回答10:

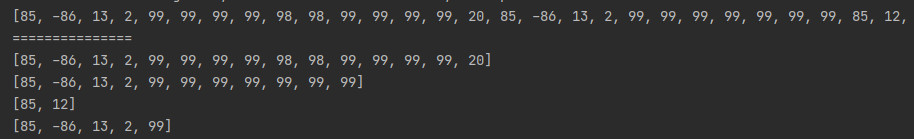

Personally for this paticular problem I tend to give passwords a 'score' based on characteristics of the entered text, and refuse passwords that don't meet the score.

For example:

Contains Lower Case Letter +1

Contains different Lower Case Letter +1

Contains Upper Case Letter +1

Contains different Upper Case Letter +1

Contains Non-Alphanumeric character: +1

Contains different Non-Alphanumeric character: +1

Contains Number: +1

Contains Non Consecutive or repeated Second Number: +1

Length less than 8: -10

Length Greater than 12: +1

Contains Dictionary word: -4

Then only allowing passwords with a score greater than 4, (and providing the user feedback as they create their password via javascript)