When you merge two branches together, git creates a separate commit with a message like Merge branch 'master' into my-branch.

For a non-trivial merge it is clear to me that this is useful: It keeps the history of how things were merged separate from any other changes. But when the merge is trivial (for example when the two branches don't affect any files in common), what is the purpose of the separate merge commit?

You can avoid that commit with git merge --no-commit. You could then add a "real" change on this commit too. That way you avoid a seemingly useless extra commit. But the man page warns about this:

You should refrain from abusing this option to sneak substantial changes into a merge commit. Small fixups like bumping release/version name would be acceptable.

Why is that?

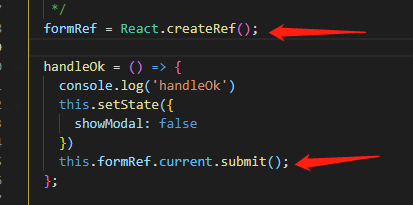

With commits with real changes in them marked as o and merge-only commits as X, this is the difference between these two situations:

o---o-o-o---o--- master

\ \ \ \

o-o-X-o-X-o-X-o--- my-feature

o---o-o-o---o--- master

\ \ \ \

o-o-o---o---o--- my-feature

Why is the first one preferred over the second one?

PS: Assume my-feature is a public branch that other people also use, so rebase would not be an option.

I think there are several reasons why having separate merge commits is a good idea, but it all comes down to the basic rule, that every commit should contain changes that belong together.

Possible situations where you will benefit from having separate merge commits:

- You're trying to find out which commit introduced a bug. If you don't separate merging and normal commits, it's hard to figure out whether the merge caused that bug, or the actual changes from that commit.

- You want to revert a change made by a commit. What should happen when you're reverting a commit that is a merge and also contains changes on its own? Do you want to revert just the changes, or just the merge, or both? If only one of them, how to separate them?

As added benefit, you get history that's easier to understand. (You could get history that's even easier to understand if you used rebase, but you said that's not possible.)

At my workplace, the "central" repository is an SVN server. I use git via git-svn.

SVN (obviously) doesn't do fast-forward merges. So, in order to be able to replicate my local history to the server, I make all merges which are going to become externally visible explicit.

The reason you would prefer this pattern in the general case (clarifying: "why would you want an explicit merge commit for a major combination of two branches, such as the reunification of a longstanding side-feature branch, even when the two don't conflict?") is that it causes the repository to better reflect the real series of operations performed - that is to say, the abstraction for history better reflects the reality of that history.

When you fast-forward, information about when the integration happened is lost - there is no point in the history saying "here is when X became Y" with an associated message.

This is the same reason some people use merges in preference to rebasing even for their local branches - rebasing is a form of history rewriting, a white-lie-on-paper.

To your other question - "why should only small changes be in a merge commit", the answer is that the merge commit may have a large diff with respect to any or all of its parents. So, if you put significant other work in there, it's very difficult to disentangle whether the problem was an integration issue or one of the new changes you added. If you put the commit either on one of the parents or after the merge, bisecting is made simpler, cherry-pick porting of the change is possible, you can reverse the merge without losing features, and so on.