I was brushing up on Tkinter when I looked upon a minimal example from the NMT Tkinter 8.5 Reference.

#!/usr/bin/env python

import tkinter as tk

class Application(tk.Frame):

def __init__(self, master=None):

tk.Frame.__init__(self, master)

self.grid()

self.createWidgets()

def createWidgets(self):

self.quitButton = tk.Button(self, text='Quit',command=self.quit)

self.quitButton.grid()

app = Application()

app.master.title('Sample application')

app.mainloop()

It's all well and good, until I notice that the Tk class isn't being initialized. In other online reference material I could find (Python's Library Reference, effbot.org, TkDocs), there's usually a call to root = tk.Tk(), from which the rest of the examples are built upon. I also didn't see any sort of reference to the Tk class initialization anywhere on the NMT's reference.

The information I could get regarding the Tk class is also vague, with the Python Reference only listing it as a "toplevel widget ... which usually is the main window of an application". Lastly, if I replace the last lines in the snippet I presented earlier:

root = tk.Tk()

app = Application(root)

The program would run as well as it did before. With all this in mind, what I'm interested in knowing is:

- What does calling

root = tk.Tk() actually do (as in, what gets initialized) and why can the previous snippet work without it?

- Would I run into any pitfalls or limitations if I don't call

Tk() and just built my application around the Frame class?

Tkinter works by starting a tcl/tk interpreter under the covers, and then translating tkinter commands into tcl/tk commands. The main window and this interpreter are intrinsically linked, and both are required for a tkinter application to work.

Creating an instance of Tk initializes this interpreter and creates the root window. If you don't explicitly initialize it, one will be implicitly created when you create your first widget.

I don't think there are any pitfalls by not initializing it yourself, but as the zen of python states, "explicit is better than implicit". Your code will be slightly easier to understand if you explicitly create the instance of Tk. It will, for instance, prevent other people from asking the same question about your code that you just asked about this other code.

Bryan Oakley's answer is spot on. Creating a widget will implicitly create an instance of the tcl/tk interpreter. I would, however, like to add some pieces of code, to better understand how Tk is implicitly created.

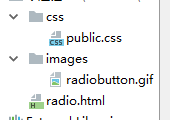

Whenever a Widget object is created (whether it is a Frame or a Button or even a ttk-based widget), the BaseWidget class' __init__ method is called, which in turn calls the _setup method. Here is a snippet of the relevant part:

def _setup(self, master, cnf):

"""Internal function. Sets up information about children."""

if _support_default_root:

global _default_root

if not master:

if not _default_root:

_default_root = Tk()

master = _default_root

self.master = master

self.tk = master.tk

Both _support_default_root and _default_root are global variables, declared in lines 132-133 of the __init__.py file in the tkinter package. They are initialized to the following values:

_support_default_root = 1

_default_root = None

This means that, if master isn't provided, and if an interpreter wasn't already created, an instance of Tk gets created and assigned as the default root for all future widgets.

There is also something interesting when creating an instance of the Tk class. The following snippet comes from the Tk._loadtk method:

if _support_default_root and not _default_root:

_default_root = self

Which means that, regardless of how the Tk class gets initialized, it is always set up as the default root.

Sometimes some widgets run Tk() on their own. But I don't know which widgets and why.

Sometimes it runs even if you don't use mainloop() - mostly on Windows.

Tkinter is strange wrapper on Tcl/Tk :)

But I prefer to use root = Tk() and root.mainloop() always.