What does the term Plain Old Java Object (POJO) mean? I couldn't find anything explanatory enough.

POJO's Wikipedia page says that POJO is an ordinary Java Object and not a special object. Now, what makes or what doesn't make and object special in Java?

The above page also says that a POJO should not have to extend prespecified classes, implement prespecified Interfaces or contain prespecified Annotations. Does that also mean that POJOs are not allowed to implement interfaces like Serializable, Comparable or classes like Applets or any other user-written Class/Interfaces?

Also, does the above policy (no extending, no implementing) means that we are not allowed to use any external libraries?

Where exactly are POJOs used?

EDIT: To be more specific, am I allowed to extend/implement classes/interfaces that are part of the Java or any external libraries?

Plain Old Java Object The name is used to emphasize that a given object is an ordinary Java Object, not a special object such as those defined by the EJB 2 framework.

class A {}

class B extends/implements C {}

Note: B is non POJO when C is kind of distributed framework class or ifc.

e.g. javax.servlet.http.HttpServlet, javax.ejb.EntityBean or J2EE extn

and not serializable/comparable. Since serializable/comparable are valid for POJO.

Here A is simple object which is independent.

B is a Special obj since B is extending/implementing C. So B object gets some more meaning from C and B is restrictive to follow the rules from C. and B is tightly coupled with distributed framework. Hence B object is not POJO from its definition.

Code using class A object reference does not have to know anything about the type of it, and It can be used with many frameworks.

So a POJO should not have to 1) extend prespecified classes and 2) Implement prespecified interfaces.

JavaBean is a example of POJO that is serializable, has a no-argument constructor, and allows access to properties using getter and setter methods that follow a simple naming convention.

POJO purely focuses on business logic and has no dependencies on (enterprise) frameworks.

It means it has the code for business logic but how this instance is created, Which service(EJB..) this object belongs to and what are its special characteristics( Stateful/Stateless) it has will be decided by the frameworks by using external xml file.

Example 1: JAXB is the service to represent java object as XML; These java objects are simple and come up with default constructor getters and setters.

Example 2: Hibernate where simple java class will be used to represent a Table. columns will be its instances.

Example 3: REST services. In REST services we will have Service Layer and Dao Layer to perform some operations over DB. So Dao will have vendor specific queries and operations. Service Layer will be responsible to call Which DAO layer to perform DB operations. Create or Update API(methods) of DAO will be take POJOs as arguments, and update that POJOs and insert/update in to DB. These POJOs (Java class) will have only states(instance variables) of each column and its getters and setters.

In practice, some people find annotations elegant, while they see XML as verbose, ugly and hard to maintain, yet others find annotations pollute the POJO model.

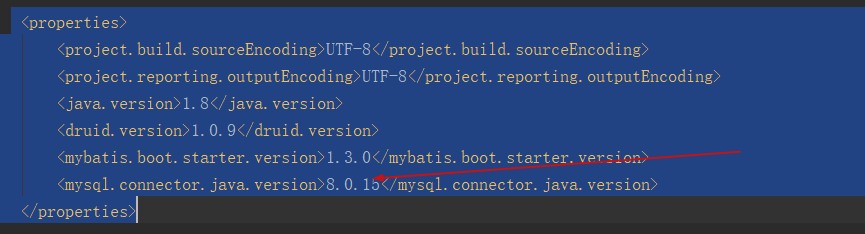

Thus, as an alternative to XML, many frameworks (e.g. Spring, EJB and JPA) allow annotations to be used instead or in addition to XML:

Advantages:

Decoupling the application code from the infrastructure frameworks is one of the many benefits of using POJOs. Using POJOs future proofs your application's business logic by decoupling it from volatile, constantly evolving infrastructure frameworks. Upgrading to a new version or switching to a different framework becomes easier and less risky. POJOs also make testing easier, which simplifies and accelerates development. Your business logic will be clearer and simpler because it won't be tangled with the infrastructure code

References : wiki source2

According to Martin Fowler, he and some others came up with it as a way to describe something which was a standard class as opposed to an EJB etc.

Usage of the term implies what it's supposed to tell you. If, for example, a dependency injection framework tells you that you can inject a POJO into any other POJO they want to say that you do not have to do anything special: there is no need to obey any contracts with your object, implement any interfaces or extend special classes. You can just use whatever you've already got.

UPDATE To give another example: while Hibernate can map any POJO (any object you created) to SQL tables, in Core Data (Objective C on the iPhone) your objects have to extend NSManagedObject in order for the system to be able to persist them to a database. In that sense, Core Data cannot work with any POJO (or rather POOCO=PlainOldObjectiveCObject) while Hibernate can. (I might not by 100% correct re Core Data since I just started picking it up. Any hints / corrections are welcome :-) ).

Plain Old Java Object :)

Well, you make it sound like those are all terrible restrictions.

In the usual context where POJO is/are used, it's more like a benefit:

It means that whatever library/API you're working with is perfectly willing to work with Java objects that haven't been doctored or manhandled in any way, i.e. you don't have to do anything special to get them to work.

For example, the XStream XML processor will (I think) happily serialize Java classes that don't implement the Serializable interface. That's a plus! Many products that work with data objects used to force you to implement SomeProprietaryDataObject or even extend an AbstractProprietaryDataObject class. Many libraries will expect bean behavior, i.e. getters and setters.

Usually, whatever works with POJOs will also work with not-so-PO-JO's. So XStream will of course also serialize Serializable classes.

POJO is a Plain Old Java Object - as compared to something needing Enterprise Edition's (J2EE) stuff (beans etc...).

POJO is not really a hard-and-fast definition, and more of a hand-wavy way of describing "normal" non-enterprise Java Objects. Whether using an external library or framework makes an object POJO or not is kind of in the eye of the beholder, largely depending on WHAT library/framework, although I'd venture to guess that a framework would make something less of a POJO

The whole point of a POJO is simplicity and you appear to be assuming its something more complicated than it appears.

If a library supports a POJO, it implies an object of any class is acceptible. It doesn't mean the POJO cannot have annotations/interface or that they won't be used if they are there, but it is not a requirement.

IMHO The wiki-page is fairly clear. It doesn't say a POJO cannot have annotations/interfaces.

A Plain Old Java Object (POJO) that contains all of the business logic for your extension.

Exp. Pojo which contains a single method

public class Extension {

public static void logInfo(String message) {

System.out.println(message);

}

}

What does the term Plain Old Java Object (POJO) mean?

POJO was coined by Martin Fowler, Rebecca Parsons and Josh Mackenzie when they were preparing for a talk at a conference in September 2000. Martin Fowler in Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture explains how to implement a Domain Model pattern in Java. After enumerating some of disadvantages of using EJB Entity Beans:

There's always a lot of heat generated when people talk about

developing a Domain Model in J2EE. Many of the teaching materials and

introductory J2EE books suggest that you use entity beans to develop a

domain model, but there are some serious problems with this approach,

at least with the current (2.0) specification.

Entity beans are most useful when you use Container Managed

Persistence (CMP)...

Entity beans can't be re-entrant. That is, if you call out from one

entity bean into another object, that other object (or any object it

calls) can't call back into the first entity bean...

...If you have remote objects with fine-grained interfaces you get

terrible performance...

To run with entity beans you need a container and a database

connected. This will increase build times and also increase the time

to do test runs since the tests have to execute against a database.

Entity beans are also tricky to debug.

As an alternative, he proposed to use Regular Java Objects for Domain Model implementation:

The alternative is to use normal Java objects, although this often

causes a surprised reaction—it's amazing how many people think that

you can't run regular Java objects in an EJB container. I've come to

the conclusion that people forget about regular Java objects because

they haven't got a fancy name. That's why, while preparing for a talk

in 2000, Rebecca Parsons, Josh Mackenzie, and I gave them one: POJOs

(plain old Java objects). A POJO domain model is easy to put together,

is quick to build, can run and test outside an EJB container, and is

independent of EJB (maybe that's why EJB vendors don't encourage you

to use them).