What is the difference between defining an object using the new operator vs defining a standalone object by extending the class?

More specifically, given the type class GenericType { ... }, what is the difference between val a = new GenericType and object a extends GenericType?

As a practical matter, object declarations are initialized with the same mechanism as new in the bytecode. However, there are quite a few differences:

object as singletons -- each belongs to a class of which only one instance exists;object is lazily initialized -- they'll only be created/initialized when first referred to;- an

object and a class (or trait) of the same name are companions;

- methods defined on

object generate static forwarders on the companion class;

- members of the

object can access private members of the companion class;

- when searching for implicits, companion objects of relevant* classes or traits are looked into.

These are just some of the differences that I can think of right of the bat. There are probably others.

* What are the "relevant" classes or traits is a longer story -- look up questions on Stack Overflow that explain it if you are interested. Look at the wiki for the scala tag if you have trouble finding them.

object definition (whether it extends something or not) means singleton object creation.

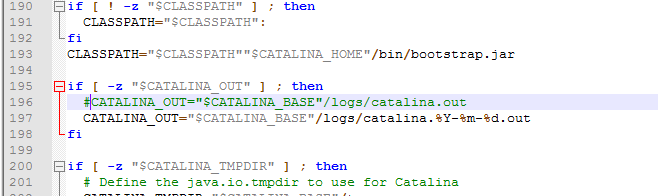

scala> class GenericType

defined class GenericType

scala> val a = new GenericType

a: GenericType = GenericType@2d581156

scala> val a = new GenericType

a: GenericType = GenericType@71e7c512

scala> object genericObject extends GenericType

defined module genericObject

scala> val a = genericObject

a: genericObject.type = genericObject$@5549fe36

scala> val a = genericObject

a: genericObject.type = genericObject$@5549fe36

While object declarations have a different semantic than a new expression, a local object declaration is for all intents and purpose the same thing as a lazy val of the same name. Consider:

class Foo( name: String ) {

println(name+".new")

def doSomething( arg: Int ) {

println(name+".doSomething("+arg+")")

}

}

def bar( x: => Foo ) {

x.doSomething(1)

x.doSomething(2)

}

def test1() {

lazy val a = new Foo("a")

bar( a )

}

def test2() {

object b extends Foo("b")

bar( b )

}

test1 defines a as a lazy val initialized with a new instance of Foo, while test2 defines b as an object extending Foo.

In essence, both lazily create a new instance of Foo and give it a name (a/b).

You can try it in the REPL and verify that they both behave the same:

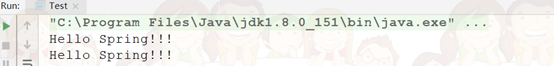

scala> test1()

a.new

a.doSomething(1)

a.doSomething(2)

scala> test2()

b.new

b.doSomething(1)

b.doSomething(2)

So despite the semantic differences between object and a lazy val (in particular the special treatment of object's by the language, as outlined by Daniel C. Sobral),

a lazy val can always be substituted with a corresponding object (not that it's a very good practice), and the same goes for a lazy val/object that is a member of a class/trait.

The main practical difference I can think of will be that the object has a more specific static type: b is of type b.type (which extends Foo) while a has exactly the type Foo.