可以将文章内容翻译成中文,广告屏蔽插件可能会导致该功能失效(如失效,请关闭广告屏蔽插件后再试):

问题:

This question already has answers here:

Closed 7 years ago.

Possible Duplicate:

typesafe NotifyPropertyChanged using linq expressions

I'm working on a large team application which is suffering from heavy use of magic strings in the form of NotifyPropertyChanged("PropertyName"), - the standard implementation when consulting Microsoft. We're also suffering from a great number of misnamed properties (working with an object model for a computation module that has hundreds of stored calculated properties) - all of which are bound to the UI.

My team experiences many bugs related to property name changes leading to incorrect magic strings and breaking bindings. I wish to solve the problem by implementing property changed notifications without using magic strings. The only solutions I've found for .Net 3.5 involve lambda expressions. (for example: Implementing INotifyPropertyChanged - does a better way exist?)

My manager is extremely worried about the performance cost of switching from

set { ... OnPropertyChanged("PropertyName"); }

to

set { ... OnPropertyChanged(() => PropertyName); }

where the name is extracted from

protected virtual void OnPropertyChanged<T>(Expression<Func<T>> selectorExpression)

{

MemberExpression body = selectorExpression.Body as MemberExpression;

if (body == null) throw new ArgumentException("The body must be a member expression");

OnPropertyChanged(body.Member.Name);

}

Consider an application like a spreadsheet where when a parameter changes, approximately a hundred values are recalculated and updated on the UI in real-time. Is making this change so expensive that it will impact the responsiveness of the UI? I can't even justify testing this change right now because it would take about 2 days worth of updating property setters in various projects and classes.

回答1:

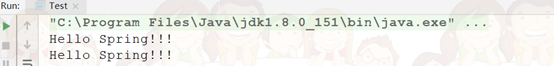

I did a thorough test of NotifyPropertyChanged to establish the impact of switching to the lambda expressions.

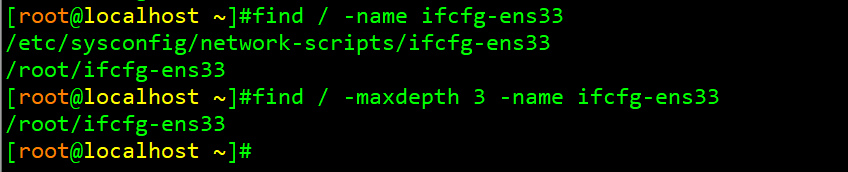

Here were my test results:

As you can see, using the lambda expression is roughly 5 times slower than the plain hard-coded string property change implementation, but users shouldn't fret, because even then it's capable of pumping out a hundred thousand property changes per second on my not so special work computer. As such, the benefit gained from no longer having to hard-code strings and being able to have one-line setters that take care of all your business far outweighs the performance cost to me.

Test 1 used the standard setter implementation, with a check to see that the property had actually changed:

public UInt64 TestValue1

{

get { return testValue1; }

set

{

if (value != testValue1)

{

testValue1 = value;

InvokePropertyChanged("TestValue1");

}

}

}

Test 2 was very similar, with the addition of a feature allowing the event to track the old value and the new value. Because this features was going to be implicit in my new base setter method, I wanted to see how much of the new overhead was due to that feature:

public UInt64 TestValue2

{

get { return testValue2; }

set

{

if (value != testValue2)

{

UInt64 temp = testValue2;

testValue2 = value;

InvokePropertyChanged("TestValue2", temp, testValue2);

}

}

}

Test 3 was where the rubber met the road, and I get to show off this new beautiful syntax for performing all observable property actions in one line:

public UInt64 TestValue3

{

get { return testValue3; }

set { SetNotifyingProperty(() => TestValue3, ref testValue3, value); }

}

Implementation

In my BindingObjectBase class, which all ViewModels end up inheriting, lies the implementation driving the new feature. I've stripped out the error handling so the meat of the function is clear:

protected void SetNotifyingProperty<T>(Expression<Func<T>> expression, ref T field, T value)

{

if (field == null || !field.Equals(value))

{

T oldValue = field;

field = value;

OnPropertyChanged(this, new PropertyChangedExtendedEventArgs<T>(GetPropertyName(expression), oldValue, value));

}

}

protected string GetPropertyName<T>(Expression<Func<T>> expression)

{

MemberExpression memberExpression = (MemberExpression)expression.Body;

return memberExpression.Member.Name;

}

All three methods meet at the OnPropertyChanged routine, which is still the standard:

public virtual void OnPropertyChanged(object sender, PropertyChangedEventArgs e)

{

PropertyChangedEventHandler handler = PropertyChanged;

if (handler != null)

handler(sender, e);

}

Bonus

If anyone's curious, the PropertyChangedExtendedEventArgs is something I just came up with to extend the standard PropertyChangedEventArgs, so an instance of the extension can always be in place of the base. It leverages knowledge of the old value when a property is changed using SetNotifyingProperty, and makes this information available to the handler.

public class PropertyChangedExtendedEventArgs<T> : PropertyChangedEventArgs

{

public virtual T OldValue { get; private set; }

public virtual T NewValue { get; private set; }

public PropertyChangedExtendedEventArgs(string propertyName, T oldValue, T newValue)

: base(propertyName)

{

OldValue = oldValue;

NewValue = newValue;

}

}

回答2:

Personally I like to use Microsoft PRISM's NotificationObject for this reason, and I would guess that their code is reasonably optimized since it's created by Microsoft.

It allows me to use code such as RaisePropertyChanged(() => this.Value);, in addition to keeping the "Magic Strings" so you don't break any existing code.

If I look at their code with Reflector, their implementation can be recreated with the code below

public class ViewModelBase : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

// Fields

private PropertyChangedEventHandler propertyChanged;

// Events

public event PropertyChangedEventHandler PropertyChanged

{

add

{

PropertyChangedEventHandler handler2;

PropertyChangedEventHandler propertyChanged = this.propertyChanged;

do

{

handler2 = propertyChanged;

PropertyChangedEventHandler handler3 = (PropertyChangedEventHandler)Delegate.Combine(handler2, value);

propertyChanged = Interlocked.CompareExchange<PropertyChangedEventHandler>(ref this.propertyChanged, handler3, handler2);

}

while (propertyChanged != handler2);

}

remove

{

PropertyChangedEventHandler handler2;

PropertyChangedEventHandler propertyChanged = this.propertyChanged;

do

{

handler2 = propertyChanged;

PropertyChangedEventHandler handler3 = (PropertyChangedEventHandler)Delegate.Remove(handler2, value);

propertyChanged = Interlocked.CompareExchange<PropertyChangedEventHandler>(ref this.propertyChanged, handler3, handler2);

}

while (propertyChanged != handler2);

}

}

protected void RaisePropertyChanged(params string[] propertyNames)

{

if (propertyNames == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException("propertyNames");

}

foreach (string str in propertyNames)

{

this.RaisePropertyChanged(str);

}

}

protected void RaisePropertyChanged<T>(Expression<Func<T>> propertyExpression)

{

string propertyName = PropertySupport.ExtractPropertyName<T>(propertyExpression);

this.RaisePropertyChanged(propertyName);

}

protected virtual void RaisePropertyChanged(string propertyName)

{

PropertyChangedEventHandler propertyChanged = this.propertyChanged;

if (propertyChanged != null)

{

propertyChanged(this, new PropertyChangedEventArgs(propertyName));

}

}

}

public static class PropertySupport

{

// Methods

public static string ExtractPropertyName<T>(Expression<Func<T>> propertyExpression)

{

if (propertyExpression == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException("propertyExpression");

}

MemberExpression body = propertyExpression.Body as MemberExpression;

if (body == null)

{

throw new ArgumentException("propertyExpression");

}

PropertyInfo member = body.Member as PropertyInfo;

if (member == null)

{

throw new ArgumentException("propertyExpression");

}

if (member.GetGetMethod(true).IsStatic)

{

throw new ArgumentException("propertyExpression");

}

return body.Member.Name;

}

}

回答3:

If you're concerned that the lambda-expression-tree solution might be too slow, then profile it and find out. I suspect the time spent cracking open the expression tree would be quite a bit smaller than the amount of time the UI will spend refreshing in response.

If you find that it is too slow, and you need to use literal strings to meet your performance criteria, then here's one approach I've seen:

Create a base class that implements INotifyPropertyChanged, and give it a RaisePropertyChanged method. That method checks whether the event is null, creates the PropertyChangedEventArgs, and fires the event -- all the usual stuff.

But the method also contains some extra diagnostics -- it does some Reflection to make sure that the class really does have a property with that name. If the property doesn't exist, it throws an exception. If the property does exist, then it memoizes that result (e.g. by adding the property name to a static HashSet<string>), so it doesn't have to do the Reflection check again.

And there you go: your automated tests will start failing as soon as you rename a property but fail to update the magic string. (I'm assuming you have automated tests for your ViewModels, since that's the main reason to use MVVM.)

If you don't want to fail quite as noisily in production, you could put the extra diagnostic code inside #if DEBUG.

回答4:

Actually we discussed this aswell for our projects and talked alot about the pros and cons. In the end, we decided to keep the regular method but used a field for it.

public class MyModel

{

public const string ValueProperty = "Value";

public int Value

{

get{return mValue;}

set{mValue = value; RaisePropertyChanged(ValueProperty);

}

}

This helps when refactoring, keeps our performance and is especially helpful when we use PropertyChangedEventManager, where we would need the hardcoded strings again.

public bool ReceiveWeakEvent(Type managerType, object sender, System.EventArgs e)

{

if(managerType == typeof(PropertyChangedEventManager))

{

var args = e as PropertyChangedEventArgs;

if(sender == model)

{

if (args.PropertyName == MyModel.ValueProperty)

{

}

return true;

}

}

}

回答5:

One simple solution is to simply pre-process all files before compilation, detect the OnPropertyChanged calls that are defined in set { ... } blocks, determine the property name and fix the name parameter accordingly.

You could do this using an ad-hoc tool (that would be my recommendation), or use a real C# (or VB.NET) parser (like those which can be found here: Parser for C#).

I think it's reasonable way to do it. Of course, it's not very elegant nor smart, but it has zero runtime impact, and follows Microsoft rules.

If you want to save some compile time, you could have both ways using compilation directives, like this:

set

{

#if DEBUG // smart and fast compile way

OnPropertyChanged(() => PropertyName);

#else // dumb but efficient way

OnPropertyChanged("MyProp"); // this will be fixed by buid process

#endif

}