What is still unclear for is what's the advantage by-name parameters over anonymous functions in terms of lazy evaluation and other benefits if any:

def func1(a: => Int)

def func2(a: () => Int)

When should I use the first and when the second one?

This is not the copy of What's the difference between => , ()=>, and Unit=>

Laziness is the same in the both cases, but there are slight differences. Consider:

def generateInt(): Int = { ... }

def byFunc(a: () => Int) { ... }

def byName(a: => Int) { ... }

// you can pass method without

// generating additional anonymous function

byFunc(generateInt)

// but both of the below are the same

// i.e. additional anonymous function is generated

byName(generateInt)

byName(() => generateInt())

Functions with call-by-name however is useful for making DSLs. For instance:

def measured(block: ⇒ Unit): Long = {

val startTime = System.currentTimeMillis()

block

System.currentTimeMillis() - startTime

}

Long timeTaken = measured {

// any code here you like to measure

// written just as there were no "measured" around

}

def func1(a: => Int) {

val b = a // b is of type Int, and it`s value is the result of evaluation of a

}

def func2(a: () => Int) {

val b = a // b is of type Function0 (is a reference to function a)

}

An example might give a pretty thorough tour of the differences.

Consider that you wanted to write your own version of the veritable while loop in Scala. I know, I know... using while in Scala? But this isn't about functional programming, this is an example that demonstrates the topic well. So hang with me. We'll call our own version whyle. Furthermore, we want to implement it without using Scala's builtin while. To pull that off we can make our whyle construct recursive. Also, we'll add the @tailrec annotation to make sure that our implementation can be used as a real-world substitute for the built-in while. Here's a first go at it:

@scala.annotation.tailrec

def whyle(predicate: () => Boolean)(block: () => Unit): Unit = {

if (predicate()) {

block()

whyle(predicate)(block)

}

}

Let's see how this works. We can pass in parameterized code blocks to whyle. The first is the predicate parameterized function. The second is the block parameterized function. How would we use this?

What we want is for our end user to use the whyle just like you would the while control structure:

// Using the vanilla 'while'

var i = 0

while(i < args.length) {

println(args(i))

i += 1

}

But since our code blocks are parameterized, the end-user of our whyle loop must add some ugly syntactic sugar to get it to work:

// Ouch, our whyle is hideous

var i = 0

whyle( () => i < args.length) { () =>

println(args(i))

i += 1

}

So. It appears that if we want the end-user to be able to call our whyle loop in a more familiar, native looking style, we'll need to use parameterless functions. But then we have a really big problem. As soon as you use parameterless functions, you can no longer have your cake and eat it too. You can only eat your cake. Behold:

@scala.annotation.tailrec

def whyle(predicate: => Boolean)(block: => Unit): Unit = {

if (predicate) {

block

whyle(predicate)(block) // !!! THIS DOESN'T WORK LIKE YOU THINK !!!

}

}

Wow. Now the user can call our whyle loop the way they expect... but our implementation doesn't make any sense. You have no way of both calling a parameterless function and passing the function itself around as a value. You can only call it. That's what I mean by only eating your cake. You can't have it, too. And therefore our recursive implementation now goes out the window. It only works with the parameterized functions which is unfortunately pretty ugly.

We might be tempted at this point to cheat. We could rewrite our whyle loop to use Scala's built-in while:

def whyle(pred: => Boolean)(block: => Unit): Unit = while(pred)(block)

Now we can use our whyle exactly like while, because we only needed to be able to eat our cake... we didn't need to have it, too.

var i = 0

whyle(i < args.length) {

println(args(i))

i += 1

}

But we cheated! Actually, here's a way to have our very own tail-optimized version of the while loop:

def whyle(predicate: => Boolean)(block: => Unit): Unit = {

@tailrec

def whyle_internal(predicate2: () => Boolean)(block2: () => Unit): Unit = {

if (predicate2()) {

block2()

whyle_internal(predicate2)(block2)

}

}

whyle_internal(predicate _)(block _)

}

Can you figure out what we just did?? We have our original (but ugly) parameterized functions in the inner function here. We have it wrapped with a function that takes as arguments parameterless functions. It then calls the inner function and converts the parameterless functions into parameterized functions (by turning them into partially applied functions).

Let's try it out and see if it works:

var i = 0

whyle(i < args.length) {

println(args(i))

i += 1

}

And it does!

Thankfully, since in Scala we have closures we can clean this up big time:

def whyle(predicate: => Boolean)(block: => Unit): Unit = {

@tailrec

def whyle_internal: Unit = {

if (predicate) {

block

whyle_internal

}

}

whyle_internal

}

Cool. Anyways, those are some really big differences between parameterless and parameterized functions. I hope this gives you some ideas!

The two formats are used interchangeably, but there are some cases where we can use only one of theme.

let's explain by example, suppose that we need to define a case class with two parameters :

{

.

.

.

type Action = () => Unit;

case class WorkItem(time : Int, action : Action);

.

.

.

}

as we can see, the second parametre of the WorkItem class has a type Action.

if we try to replace this parameter with the other format =>,

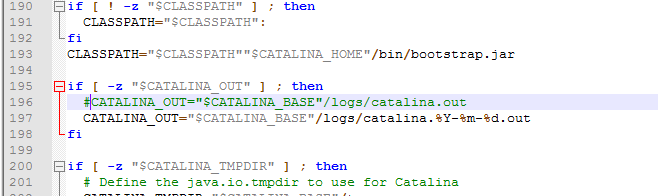

case class WorkItem1(time : Int, s : => Unit) the compiler will show a message error :

Multiple markers at this line:

`val' parameters may not be call-by-name Call-by-name parameter

creation: () ⇒

so as we have see the format ()=> is more generic and we can use it to define Type, as class field or method parameter, in the other side => format can used as method parameter but not as class field.

A by-name type, in which the empty parameter list, (), is left out, is only

allowed for parameters. There is no such thing as a by-name variable or a

by-name field.

You should use the first function definition if you want to pass as the argument an Int by name.

Use the second definition if you want the argument to be a parameterless function returning an Int.