可以将文章内容翻译成中文,广告屏蔽插件可能会导致该功能失效(如失效,请关闭广告屏蔽插件后再试):

问题:

I have a Perl script that forks.

Each fork runs an external program, parses the output, and converts the output to a Storable file.

The Storable files are then read in by the parent and the total data from each of the children are analyzed before proceeding onto a repeat of the previous fork or else the parent stops.

What exactly happens when I issue a ^C while some of the children are still running the external program? The parent perl script was called in the foreground and, I presume, remained in the foreground despite the forking.

Is the SIGINT passed to all children, that is, the parent, the parent's children, and the external program called by the children??

UPDATE:

I should add, it appears that when I issue the SIGINIT, the external program called by the children of my script seem to acknowledge the signal and terminate. But the children, or perhaps the parent program, carry on. This is all unclear to me.

UPDATE 2:

With respect to tchrist's comment, the external program is called with Perl's system() command.

In fact, tchrist's comment also seems to contain the explanation I was looking for. After some more debugging, based on the behavior of my program, it appears that, indeed, SIGINT is being passed from the parent to all children and from all children to all of their children (the external program).

Thus, what appears to be happening, based on tchrist's comment, is that CTRL-C is killing the external program which causes the children to move out of the system() command - and nothing more.

Although I had my children check the exit status of what was called in system(), I was assuming that a CTRL-C would kill everything from the parent down, rather than lead to the creation of more rounds of processing, which is what was happening!!!

SOLUTION (to my problem):

I need to just create a signal handler for SIGINT in the parent. The signal handler would then send SIGTERM to each of the children (which I presume would also send a SIGTERM to the children's children), and then cause the parent to exit gracefully. Although this somewhat obvious solution likely would have fixed things, I wanted to understand my misconception about the behavior of SIGINT with respect to forking in Perl.

回答1:

Perl’s builtin system function works just like the C system(3) function from the standard C library as far as signals are concerned. If you are using Perl’s version of system() or pipe open or backticks, then the parent — the one calling system rather than the one called by it — will IGNORE any SIGINT and SIGQUIT while the children are running. If you’ve you rolled your own using some variant of the fork?wait:exec trio, then you must think about these matters yourself.

Consider what happens when you use system("vi somefile") and hit ^C during a long search in vi: only vi takes a (nonfatal) SIGINT; the parent ignores it. This is correct behavior. That’s why C works this way, and that’s why Perl works this way.

The thing you have to remember is that just because a ^C sends a SIGINT to all processes in the foregrounded process group (even those of differing effective UID or GID), that does not mean that it causes all those processes to exit. A ^C is only a SIGINT, meant to interrupt a process, not a SIGKILL, meant to terminate with no questions asked.

There are many sorts of program that it would be wrong to just kill off with no warning; an editor is just one such example. A mailer might be another. Be exceedingly careful about this.

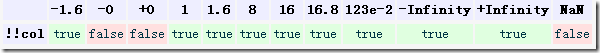

Many sorts of programs selectively ignore, trap, or block (means delay delivery of) various sorts of signals. Only the default behavior of SIGINT is to cause the process to exit. You can find out whether this happened, and in fact which signal caused it to happen (amongst other things), with this sort of code on traditional operating systems:

if ($wait_status = system("whatever")) {

$sig_killed = $wait_status & 127;

$did_coredump = $wait_status & 128;

$exit_status = $wait_status >> 8;

# now do something based on that...

}

Note carefully that a ^C’d vi, for example, will not have a wait status word indicating it died from an untrapped SIGINT, since there wasn’t one: it caught it.

Sometimes your kids will go and have kids of their own behind your back. Messy but true. I have therefore been known, on occasion, to genocide all progeny known and unknown this way:

# scope to temporize (save+restore) any previous value of $SIG{HUP}

{

local $SIG{HUP} = "IGNORE";

kill HUP => -$$; # the killpg(getpid(), SIGHUP) syscall

}

That of course doesn’t work with SIGKILL or SIGSTOP, which are not amenable to being IGNOREd like that.

Another matter you might want to be careful of is that before the 5.8 release, signal handling in Perl has not historically been a reliably safe operation. It is now, but this is a version-dependent issue. If you haven’t yet done so, then you should definitely read up on deferred signals in the perlipc manpage, and perhaps also on the PERL_SIGNALS envariable in the perlrun manpage.

回答2:

When you hit ^C in a terminal window (or any terminal, for that matter), it will send a SIGINT to the foreground process GROUP in that terminal. Now when you start a program from the command line, its generally in its own process group, and that becomes the foreground process group. By default, when you fork a child, it will be in the same process group as the parent, so by default, the parent (top level program invoked from the command line), all its children, children's children, etc, as well as any external programs invoked by any of these (which are all just children) will all be in that same process group, so will all receive the SIGINT signal.

However, if any of those children or programs call setpgrp or setpgid or setsid, or any other call that causes the process to be a in a new progress group, those processes (and any children they start after leaving the foreground process group) will NOT receive the SIGINT.

In addition, when a process receives a SIGINT, it might not terminate -- it might be ignoring the signal, or it might catch it and do something completely different. The default signal handler for SIGINT terminates the process, but that's just the default which can be overridden.

edit

From your update, it sounds like everything is remaining in the same process group, so the signals are being delivered to everyone, as the grandchildren (the external programs) are exiting, but the children are catching and ignoring the SIGINTs. By tchrist's comment, it sounds like this is the default behavior for perl.

回答3:

If you kill the parent process, the children (and external programs running) will still run until they terminate one way or another. This can be avoided if the parent has a signal handler that catches the SIGINT, and then kills the process group (often parent's pid). That way, once the parent gets the SIGINT, it will kill all of it's children.

So to answer your question, it all depends on the implementation of the signal handler. Based on your update, it seems that the parent indeed kills it's children and then instead of terminating itself, it goes back to doing something else (think of it as a reset instead of a complete shutdown/start combination).