I have a protected branch that should only be promoted/fast-forwarded once the integration build on the integration build passes.

I currently try to solve this by having an integration build on pull requests to integration branch, that, once it succeeds, simply fast forwards the release branch to the tip of the integration branch.

However, when I build a branch on the TFS build system, it will checkout the commit at the head of the integration branch, leaving the build server in detached head state.

That should all be fine, but for some reason I can not do that without using multiple statements. To me, intuitively, there should be a simple command for this. I only want to fast-forward a branch point to the current commit.

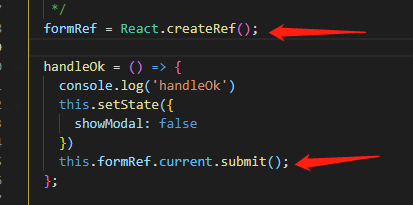

For now though, I have found 2 ways to do it:

Saving HEAD commit with scripting

- Save HEAD commit to variable in current shell scripting language (here saved to %HEAD_commit_id%)

git checkout releasegit merge %HEAD_commit_id%

Using throw-away branch

git branch current-headgit checkout releasegit merge current-headgit branch -d current-head

Looking for better solution

Is it correct that the above is "the best" I can do to accomplish this? I would think a one-line exists for this? Both solution 1 and 2 has its caveats, so I would rather go with neither, but I will probably end up with using number 2 in the end.

Steps to reproduce scenario

To reproduce the exact scenario I have, you need 2 commits (C1 and C2) and 2 branches (release and integration).

Point release to C1, integration to C2 and HEAD to C2 (detached head state).

The end result should allow me to push the release branch, now pointing to the same commit as integration.

You have many options; which to use depends what you can guarantee about your environment.

You could use (tip of the hat to jthill):

git checkout release && git merge --ff-only @{1}

(with anything your shell requires to protect the braces from expansion). That's equivalent to your first method, but does not need a temporary variable since @{1} means "the previous value of HEAD before the checkout".

You can, however, also use either of these rather tricky operations:

git push . HEAD:refs/heads/release

or:

git fetch . HEAD:refs/heads/release

as we'll see below. This is more efficient in some ways. Its main drawback is that almost no one groks it.

Background

Let's first note that each repository is self-contained, by which I mean each repository has its own branch names, and its own HEAD and index and work-tree. (The latter three—HEAD, index, and work-tree—function as a unit. If you have Git version 2.5 or later, you can use git worktree add to add independent work-trees, each of which comes with its own HEAD and index.)

git checkout name-or-ID will, assuming all goes well:

- Leave

HEAD pointing to ID, usually through name (an "attached HEAD"), but directly if necessary (when you give it an ID, or use --detach to make sure it detaches HEAD from the name you give it).

- Fill in the index from the commit

HEAD now names.

- Fill in the work-tree from this same commit.

Now, let's consider what git merge does when it's possible to fast-forward instead of actually merging. This occurs when HEAD names a commit that is an ancestor of the target commit and you tell git merge to merge with anything that identifies that target commit. The identifier you pass to git merge can be a raw hash ID (as in your %HEAD_commit_id% method), or a branch name (as in your git merge current-head method). The only thing that is necessary is that git merge:

- find the target commit (e.g., receive its hash ID or resolve a name to its hash ID);

- compute the merge base of

HEAD and the target commit; and

- discover that this merge base is the same commit that

HEAD identifies.

These are the conditions under which a fast-forward merge is possible. If a fast-forward merge is possible, and you have not forbidden it explicitly (git merge --no-ff) or implicitly (git merge -s ours for instance, or certain cases of merging using an annotated tag), git merge will do the fast-forward operation in this case. You can even add --ff-only to the arguments to git merge to tell Git: Do a fast-forward if possible, and if it's not possible, give me an error instead of doing a real merge.

The fast-forward merge operation

Now let's look at what the fast-forward merge actually does. There are multiple parts to this, because git merge affects the current (HEAD-attached) branch, or if HEAD is detached, HEAD itself. Note that if something goes wrong partway through, Git attempts to back out the entire operation, so that it looks like either everything succeeds, or the fast-forward never even starts. (In some particularly nasty cases, such as when the computer has caught fire, the messy internal state may show through, provided your computer survives the conflagration.)

Git needs to make the index and work-tree match the merge result, which is of course the target commit. So in effect, Git checks out the target commit. However, HEAD remains connected to the current branch, if it's attached. This checkout of the target commit updates the index and work-tree.

If HEAD is attached, Git now changes the branch name to which HEAD is attached so that this name identifies the commit just checked-out—the target commit. That is, if we had something we might draw this way:

...--o--o <-- branch (HEAD)

\

o--o--o <-- target_commit

\

o--...

we now have:

...--o--o

\

o--o--o <-- branch (HEAD), target_commit

\

o--...

This is the fast-forward operation in play, when we are on the given branch.

(If HEAD is detached, simply imagine the same action without the name branch in front of it.)

Consider git fetch and git push

When you use git fetch to obtain new commits from another Git, or git push to give your own commits to another Git, you have the two Gits talk to each other and transfer any new commits. Assume for the moment that this is a git fetch operation:

...--o--o--X

becomes:

...--o--o--X--Y--Z

where Y--Z are the new commits that link up with the tip commit X of our branch. Quite typically, X has two names pointing to it, such as master and origin/master, at the start of the operation:

...--o--o--X <-- master (HEAD), origin/master

and at the end, the corresponding origin/master name has moved, so we might draw the commits like this:

...--o--o--X <-- master (HEAD)

\

Y--Z <-- origin/master

Consider how the name origin/master just moved, and compare it to how branch moved when we did a fast-forward merge. These are the same motions: the name origin/master moved in a fast-forward fashion, so that instead of pointing to commit X, it now points to commit Z.

This, too, is what happens during git push, except that instead of having our Git retrieve commits from their Git, we have our commit give commits to their Git. But once we have done that, we don't want our Git to remember their Git's master, we want their Git to remember, as their master, our final commit. So if they had:

...--o--o--X <-- master

and we gave them --Y--Z that connect to X, we'd like them to make their master point to Z:

...--o--o--X--Y--Z <-- master

This, too, is a fast-forward operation.

Note that if the request we make isn't a fast-forward, the other Git generally rejects our request:

...--o--o--X--W <-- master

\

Y--Z <-- (we request that they set their master here)

In this case, if they moved their name master to point to Z, they would "forget" commit W. That's a non-fast-forward operation, and is the kind of thing that when we run git merge, causes us to get a true merge. A Git that is receiving a git push won't run git merge, so it requires that our request be a fast-forward operation—well, requires this unless we tell it to force the change.

As long as we don't use --force or equivalent, this kind of git push won't make any change that is not a fast-forward operation. The other Git will simply say: No, I won't do that, because it's not a fast-forward.

Note that unlike our fast-forward merge case, their Git—the other Git to which we are git pushing—doesn't run git checkout on any updated commit hashes. This is why we must either push to a --bare repository, which has no work-tree, or push to a branch that the other Git doesn't have checked out.1

This means we can (ab)use fetch or push

We know that:

git push will fast-forward a branch, as long as it's not checked out, and- we're in "detached HEAD" mode, so we don't have branch

release checked out, so

- what if we have our Git call up our own Git? What if we ask them to set their

release to some specific commit hash?

Our Git will ask their Git—which is really our Git, just wearing a different hat—to take any new commits—there aren't any; our Git has all the commits that our Git has—and then update its (our) release in a fast-forward manner, since we're not asking it to force anything. Hence we can fast-forward our own release to the commit identified by HEAD if we just say: Hey, other Git, set your refs/heads/release to the commit identified by my HEAD! We do that with a push refspec of the form:

HEAD:refs/heads/release

The only trick now is to call up ourselves. Normally we might need a URL, but Git allows path names, including relative path names; and the relative path name . means the current directory. So if we:

git push . HEAD:refs/heads/release

we'll have our Git call up own own Git, transfer nothing (no new commits), and ask our Git to set our refs/heads/release in a fast-forward fashion, to match our current HEAD. Since our release is not checked out, this is allowed if and only if the operation is a fast-forward.

The fetch trick is exactly the same: we fetch from ourselves (which transfers no commits), then request that our own Git set our own refs/heads/release to a specific commit hash. Since there is no leading + force-flag, this too verifies that the operation is fast-forward-only. Because we do not use --update-head-ok, this does the same check that git push does, that the current HEAD does not name branch release. Curiously, we get the hash ID from the other Git this time (but that's ourselves so it's the same hash ID either way).

1This actually depends on the setting of receive.denyCurrentBranch. See also receive.denyNonFastForwards. Newer Gits also support updateInstead with which we can have the target Git run git checkout, but only in certain circumstances; this allows non-bare repositories to be used with git push even with a branch occupying their work-tree-and-index pair.