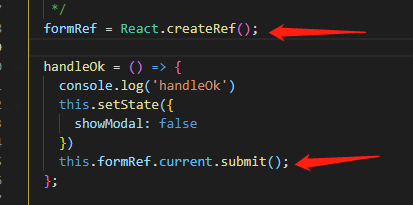

Consider the following code:

class A

{

public:

A() {}

~A() {}

};

class B: public A

{

B() {}

~B() {}

};

A* b = new B;

delete b; // undefined behaviour

My understanding is that the C++ standard says that deleting b is undefined behaviour - ie, anything could happen. But, in the real world, my experience is that ~A() is always invoked, and the memory is correctly freed.

if B introduces any class members with their own destructors, they won't get invoked, but I'm only interested in the simple kind of case above, where inheritance is used maybe to fix a bug in one class method for which source code is unavailable.

Obviously this isn't going to be what you want in non-trivial cases, but it is at least consistent. Are you aware of any C++ implementation where the above does NOT happen, for the code shown?

This is a never-ending question in the C++ tag: "What is the predictable undefined behavior". Easy to resolve all by yourself: get every C++ compiler implementation and check if the predictable unpredictable still works. This is however something you have to do by yourself.

Do post back what you found out, that would be quite useful to know. As long as the unpredictable has consistent and annotated behavior across the board. It makes it really hard for somebody that writes a C++ compiler to get anybody to pay attention to his product. Standardization by convention, happens a lot with a language that has a lot of undefined behavior.

As far as I know, there's no implementation where that's not true. On the other hand, having a class where if you put a non-POD in it, it blows up, is the kind of bad thing that it's hardly unreasonable to describe as a bug.

In addition, your question title is incredibly misleading. Yes, it is a serious real world problem to not invoke a class's destructor. Yes, if you restrict the input set to an incredible minority of real world classes, it's not a problem.

Class B will almost always be larger than A in non-trivial cases, because it has an instance of A inside it as well as the additional members of B. It gets worse when you introduce virtual members.

So while ~A will get called, it is easy to see that this kind of thing can result in a memory leak. It is undefined behaviour not because it may not call ~A, that is basically guaranteed, but by how the memory is managed.

"For the code shown" it is very unlikely you'll ever find an implementation that will act up. That is if we exclude from consideration various "debugging" implementations, which are specifically and intentionally designed to catch such errors.